By KATIE EUBANKS

Willie and Alex McClain (far left and far right) with (from left) Jermaine, Kaleb, Shannon and Brandon, whom the McClains mentor through their ministry, Partners in the Gospel.

Willie McClain doesn’t do fake.

He didn’t do fake in his previous life as part of the Aryan Brotherhood in prison. And he doesn’t do fake now at Partners in the Gospel, the fancy name for he and his wife, Alex, pouring into four young men in their downtown Jackson neighborhood.

Years ago, when a black inmate insulted one of Willie’s white “brothers” in the penitentiary, Willie was ready to fight. When some Aryan Brotherhood members, or ABs, said, “No, we can’t do that,” Willie called them out on it.

Today, when professing Christians use the n-word because they see Willie’s old swastika tattoo — a remnant of who he once was — or when they speak one way and live another, Willie calls them out on it.

Good, bad or ugly, he’s never done anything halfway.

From Aryan Brotherhood to brother in Christ

Willie grew up “really, really poor” in northeast Mississippi, he says. “Most of the (Ku Klux) Klan activity you’ve seen is probably in that area, or in Texas.”

Three or four of his relatives were members of the Klan, he says. The n-word was as common to Willie’s ears as any other phrase.

At the same time, “It’s not necessarily waking up with this vile hatred, a lot of times,” he says, pointing to his heart. “I just preferred to be with my own kind.”

His dream was to be a Hell’s Angel. He’d seen the notorious motorcycle gang on TV, and he’d seen one of his momma’s boyfriends, a member of a biker gang, after the man was shot in the leg.

“That was so cool,” Willie says. “I found my identity in that.”

By 13, he was “starting in a dope gang,” he says. By 15 he was selling multiple types of drugs. He quit school and worked for his uncle, a diesel mechanic, while growing weed and getting into fights.

At 27, in prison for the first time, he faced a question: Who are you going to ride with?

In the penitentiary, “you’re either part of a gang or you’re open for others to take from (and) abuse,” Willie says.

He had three choices as a white inmate, other than becoming fair game: The Simon City Royals; the Latin Kings, made up of white guys who “rode under” black Vice Lords; or the Aryan Brotherhood, which was “at the top of the food chain,” he says.

“I was Aryan (Brotherhood) from the door.”

He got into a fight within 30 minutes of entering prison, and he wound up fighting about once a month, sometimes a few times a month, for 29 and a half months.

That first prison stint didn’t break him. It just made him more hateful — toward everybody, he says.

But by the time he was released from his third stint in 2011, “I was getting broken … I told Jesus, ‘When I come back (to prison), I’ll give You a chance.’”

He got busted for the final time at his momma’s house in August 2012. “My momma lost her house (because of that),” he says.

In jail, “I was very sick,” he says. Sick to the point of having to crawl around. While he was crawling, “all I could say was, ‘Lord, help me.’”

A couple days later, he asked for a Bible. The next time the “preacher man” came to the prison, Willie beckoned him over and asked, “How do we do this?”

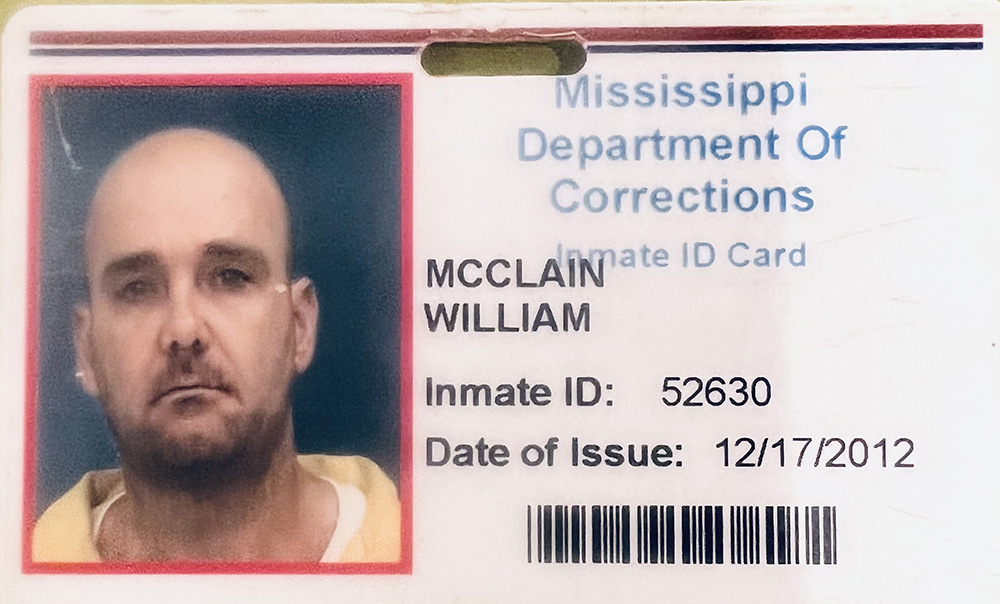

Willie’s inmate ID is one of the only surviving remnants of his former self. By spring 2013, Willie had given his life to Christ and left the Aryan Brotherhood.

Finding freedom

By spring 2013, Willie had accepted Christ and left the Aryan Brotherhood. That second part doesn’t happen easily.

“If you’re getting out, (they want to know) what’re you getting out for? If you get out and circle back around, it’s going to be bad. Or if you just say, ‘I’m getting tired of this,’ that’s not going to work out for you,” he says.

“I laid my (AB) flag down because I’d given my life to Christ.”

And they let him go.

On March 31, 2013, Willie put his name on the list to be baptized. The next day he had a work duty outside the prison. Two ABs, no longer his “brothers” but guys he was still friendly with, were in the truck with him.

“Within 15 minutes, I’m high,” he says. He shot up twice. Four hours later, during the work duty, “that’s the first time the Spirit really spoke to me.”

Willie had connections outside the prison walls, “people waiting to hear from me where to bring my dope,” he says. “I’m high, thinking, talking to my buddy … he said, ‘You want some more?’ And I said, ‘Nah, you know what, dude, I’m done.’”

Willie confessed to the “preacher man,” whose real name was Volley Davis, and “it kind of hurt his feelings,” Willie says. But then Bro. Volley asked, “What’re you going to do (now)?”

That was the last time Willie got high.

He became a model prisoner and paroled out in November 2014, just a couple years into his seven-year sentence.

He wanted the transport van to take him to his grandmother’s address, but it was denied. Willie found out “(my family was) scared — not of me, but of what comes with me,” he says.

So the van left him at a halfway house in Jackson. “Within 30 minutes, (the other guys there are) asking if I want to get high,” he says.

Thankfully, he was able to move to the Wingard Home, a Christian outreach to the homeless in Jackson.

Within a week, he found We Will Go Ministries.

Willie met Alex at We Will Go, a few months after making parole.

One human race

Six days a week, Willie worked. On Sundays, he attended Pinelake Church in the morning and We Will Go’s worship service in the afternoon.

WWG was founded by David and Amy Lancaster, suburbanites who felt called to move to downtown Jackson and start a ministry. “Ms. Amy’s real,” Willie says. “She’ll hurt your feelings if you’re not careful, but she’s real.” So Willie started helping with the Sunday services and engaging with the male missionaries at WWG.

Most of the people served by WWG are homeless — and black. What about Willie wanting to be “with his own kind”?

For somebody who used to be part of a white supremacist group, and now ministers to people who share an ethnicity he once thought he’d hate forever, Willie is not preoccupied with race. He doesn’t make speeches about reconciliation or justice. He simply lives it out. He let go of his prejudice in light of the gospel.

“Where I’ve gotten to is, how does Jesus look at people? God created you, and God created me. He created one human race,” he says. “We accept every man and every woman as someone God created.”

He does see the humor in where he landed, though. “God, do you see this tattoo? And you’re putting me in Jackson?” (For the record, he has looked into removing the symbol from his right bicep, but the procedure was going to be too painful.)

A few months after Willie made parole, a woman named Alex Hart moved from Massachusetts to Jackson to be a WWG missionary. She didn’t know what box to put Willie in.

“Willie became kind of a committed (church) member (at WWG),” she says. She wondered if he was homeless. “But I came to understand he was trying to get back on his feet.”

By the time they saw each other at the wedding of one of the WWG missionaries a year later, “I had become interested in finding out if I was interested in him,” she says.

Or in Willie’s words, “She started hitting on me.”

They were married less than six months later.

“We have a lot of differences. North, South, different education, I didn’t grow up poor,” Alex says. But they were both called to something.

Most importantly, Willie says, “We were both Jesus-centered.”

Clockwise from top left: Willie baptizing Kaleb last summer as Shannon (right) and ministry supporter Ken McKinion look on; Willie and ministry volunteer Brycen Witcher cheered on Kaleb when he won the principal’s award at school; Willie teaching the boys weightlifting; Kaleb and Jermaine cooking with Alex; Brandon showing off his catch on a fishing trip; and Shannon (center) doing the same, with Brycen (left) and Donovan Case.

‘Can they still be godly men?’

Willie started working at We Will Go, and over several years he and Alex developed relationships with four local boys, who now range from 14 to 17: Kaleb, Jermaine, Brandon and Shannon.

“We decided to invest in them (more),” Alex says, “going deep instead of wide.”

“If someone doesn’t intervene, you can check the box where they’ll end up right now,” Willie says. “In (inner-city) Jackson, you grow up in a gang. (Because) ‘Dad used to be this.’”

So now, while Alex teaches art at Richland High School, Willie is full time with Partners in the Gospel, which he and Alex started a little over a year ago. Every day after school, Willie tutors the four boys for a couple hours. On Wednesday nights, the boys come over for dinner. On some weekends, Willie might take them on an excursion like fishing or camping. He teaches them weightlifting. And of course he talks to them about Jesus.

The goal? “For them to become the men God wants them to be,” Willie says.

“That might not look like graduating high school,” Alex says. “It might look like earning a GED, finding and sticking with a career.”

Last month, Willie finagled a great educational opportunity for Kaleb, the youngest — but Kaleb quit on it after a week. Now Willie knows he needs to approach the mothers first, to see if they’ll agree with him and back him up, before pushing the boys toward a goal, such as learning the trade skills he’d like to teach them. “I did the ultimate missionary thing, (saying) ‘Here’s what you need,’ without asking them first,” he says.

So progress comes in fits and starts. One of the older guys might text Willie to apologize for bad behavior. Or Willie will ask one of them to pray on a Wednesday night, and something in their prayer will give him hope.

Willie says Shannon would stay with him 24/7 if he could. “He texts Willie if we haven’t met in a couple days,” Alex adds.

Willie’s goal for the boys he mentors is “for them to become the men God wants them to be,” he says.

The boys know about Willie’s past. But more importantly, they experience how he cares for them in the present.

Last summer, Willie got to baptize Kaleb. Of course that doesn’t mean Kaleb will never go down the wrong path.

“We’re trying to do everything we can possibly do before they leave us,” Willie says. “So later, if they do bump their head enough, they will return to Jesus. … What I would love to have is for them to become good fathers who want to get good jobs. … Maybe they’ll work a ‘regular’ job. But can they still be godly men? Yes.”

“You know you’re planting seeds,” Alex says. “When you partner with Jesus, you know you’re making a difference.”

For more information or to give to Partners in the Gospel, visit PartnersInTheGospel.org.