By Sherry Lucas

Mississippi’s Museums Tell Our Story

Gather around the circle; gather around the light. In Mississippi’s two new state-of-the-art museums that opened in December to culminate the state’s bicentennial celebration, the flame has a central spot at the heart of each.

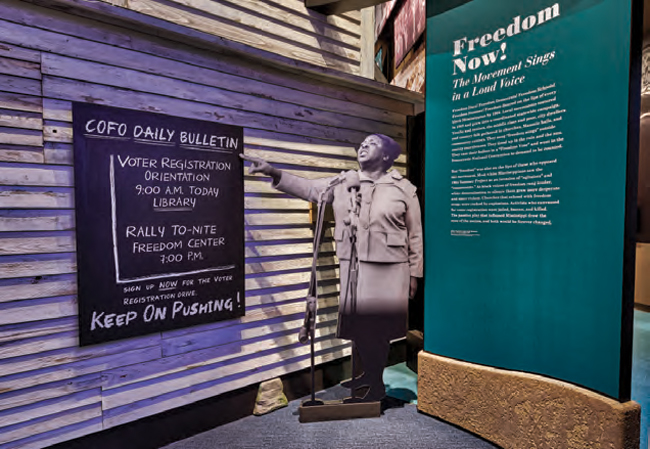

In the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum’s rotunda, a two-story fabric light sculpture of intertwining blades creates a space to reflect on the hard truths in the galleries, to remind visitors of those who led the movement and the state forward, and to inspire them to do the same.

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, Six: I Question America, gallery entryway

In the Museum of Mississippi History, the orientation theater’s campfire scene sets the tone for stories shared, prehistory to the present, from all the cultures that gave them voice.

The two museums, funded by $90 million from the Mississippi Legislature and an additional $19 million in private donations for exhibits and endowments, share the state’s history, painful and proud. Linked by a lobby and also sharing auditorium, classroom space, and more, the facility covers 200,000 square feet.

Museum of Mississippi History, Scenic Overlook, “One Mississippi, Many Stories”

In each, layered displays with strong audio-visual components and hands-on, sit-in and walk-through experiences reach out to touch nearly every sense, making the history more memorable, more vivid, and more keenly felt. It’s a collage that begs for repeat visits to fully digest the scope and depth.

The Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, the nation’s only state-run civil rights museum, is one where “you are awed when you walk in and changed when you walk out,” museum director Pamela Junior says. “We want people to see Mississippi in this light, and then to be able to come out with emphasis on changing their lives, doing better, and making this state the best state that it can be.”

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, Six: I Question America, “Is This America?”

The accurate history of violence, oppression, and injustice is an uncomfortable past to confront and tight spaces, sharp angles, and angry, condescending voices reinforce that. At the outset, a note to visitors alerts them that quotes and documents contain offensive images and language. Warning signs indicate graphic content. But inside the galleries, reading the names of known lynching victims on the monoliths, seeing the degrading imagery of the Jim Crow era, and the ominous sight of a Klansman’s robe and a tiny coffin (an intimidation tool) illuminate the brutal history that made Mississippi ground zero for the civil rights movement.

In displays that resemble shattered windows are the stories of bombs in Natchez, a riot in Clinton, a gun battle in Jackson. You might catch your reflection in a red-mirrored shard. Small theaters recount harrowing events—the kidnapping and murder of Emmett Till, the assassination of Medgar Evers, and the murders of the civil rights workers Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner—in forthright ways that bring their impact home, on the human and the historic scale. “Lord have mercy,” came the haunting sigh of a visitor in the Emmett Till theater.

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, Four: A Closed Society, “The Lynching of Emmett Till”

Enter a schoolhouse to get a better feel for segregation and the emptiness of the “separate but equal” claim. Sit in the paddy wagon or jail to get a sense of the struggle for those on the movement’s front lines. Look closely at the bullet holes in a panel from slain activist Vernon Dahmer’s truck, in which his family fled the Klan’s firebombing of their home. Duck into a church sanctuary to renew the sustaining power of faith. Step into the rotunda—Gallery 3’s “The Little Light of Mine”—to reflect, absorb, hear songs that shared strength and see the names and faces of heroes of the movement.

Threads of inspiration and support weave through the galleries, too—all the more courageous for their setting amid such struggle. Visitors enveloped by “Why we march” panels—for children, against fear, for justice—have a galvanizing effect and the final gallery carries that hopeful spirit forward with a challenge, “Where do we go from here?”

In the Museum of Mississippi History, native cultures, European settlers, enslaved people later freed, and immigrants all populate the state and have voice in its story. As told through artifacts, art, scenes, and displays, it’s one richly illustrated and vibrantly shared.

Museum of Mississippi History, Forging Ahead 1946–Present, “Lucille’s Place Juke Joint”

Wealth and poverty, achievement and loss, war and service, disaster and recovery are part of the history of Indian removal, cotton kingdom, Civil War and Reconstruction, the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, hurricanes, and the musicians, writers, and artists who capture the soul of the state.

Details as small as an arrowhead or a mosquito through a microscope are portals for the larger picture of first peoples’ innovation or the impact of malaria and yellow fever that plagued Mississippians until the mid-20th century. Large exhibits invite visitors into an inn along the Natchez Trace, close to a cotton barge on the Mississippi River and into a juke joint where the jukebox’s Staples Singers selection promises “I’ll Take You There.”

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, Five: A Tremor In The Iceberg, “Medgar Evers Assassinated”

Visitors can mail a postcard, design a flag, or a quilt block, hear stories in the voices of everyday people and even share their own.

Both museums contribute significantly to a better understanding of Mississippi’s past and its place. “One is not complete without the other,” Myrlie Evers, widow of slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers, said at the museums’ grand opening Dec. 9.

“Both buildings share the same heart, share the same beat of humanity. And it is my hope that not only in Mississippi, not only in America, but across this world, people will come here to study about humanity, to study about how we have made progress, how we can set a role for others to follow.

Sherry Lucas is a freelance feature writer, copywriter and copy editor with 30-plus years of reporting and writing experience and a passion for sharing Mississippi’s cultural wealth. Email her at sherrylucas7@gmail.com.