By MARILYN TINNIN

Central Mississippi will have a rare opportunity this August 7–9. The Mississippi Humanities Council and the Bob Woodruff Foundation have partnered with New Stage Theatre to present The Telling Project.

After weeks of rehearsal with an acting coach, five local veterans and one niece of a fallen soldier will share unique experiences. You will come away with a great eye-opening appreciation for the sacrifices, the courage, and the superhuman love of country displayed here.

The Telling Project will be produced all over the country with the cast selected from each local community. It is an intimate and profoundly powerful production.

There is no ticket to purchase to attend one of these performances, but neither can you reserve a seat. So be there early! This is a true gift to all of us.

It has never been more important than in this present moment to hear their stories and to understand exactly the cost—as well as the gift—that is ours as Americans. In the same way the Israelites were instructed in Deuteronomy 4:9 to share the account of their deliverance from Egyptian oppression, it is our duty to pass on the stories of freedom to the next generation.

Our freedom as Americans is a great blessing and a great gift. Freedom is never “free” for those who serve in the armed forces.

Troy D. Morgan, Jr.

Just outside the Civil Engineering Compound in Kyrgystan at Manas International Airport. A poignant reminder of the price of freedom.

Troy Morgan is a Brookhaven resident who entered the Air Force in 2003 as an Airman First Class. He served in Operation Iraqi Freedom, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation New Dawn.

He was assigned to Pest Control as a Civil Engineer. Pest Management is a huge concern because a rodent or a bird carrying an infectious disease could have catastrophic effects and seriously hamper the readiness, health, and safety of an entire base. Troy’s task was to make sure the bugs and the animals stayed in check and that the troops were ready to perform. He says with a laugh, “I was kind of a glorified Orkin man!”

Like the character in the 1989 movie by the same name, Troy was Born on the Fourth of July. He is an Eagle Scout; so, it is natural that he was drawn to the values of the military. He was proud to serve his country, but no amount of training can fully prepare an eager soldier for the realities of war. Even though he never had to carry a weapon or kill anyone, the sights and sounds he experienced left him with moderate PTSD and knees that will never be the same.

He speaks of hundreds and hundreds of animals his group had to put down, but animal control was necessary. The enemy went so far as to stitch grenade-like explosives inside puppies and detonated them by calling from a go-phone. Such horrendous images are difficult to forget.

Retired in 2012, Troy was interested in The Telling Project because “I have a real heart for veterans,” and because he sees it as “another healing opportunity to heal in a different way. It’s important to hear the stories and for things to not be superficial.”

He is a man of deep faith who is not shy about professing his love for Christ. He says, “I would do it again. I tear up when I think about the flag furling. I love my country.”

Dr. Ken Oswalt

Today Dr. Oswalt practices anesthesiology at University Medical Center. He served as a naval physician during the Cold War from 1976 to 1988 and is quick to say, “It is important for people to realize that even in peacetime, the military makes huge personal sacrifices when it comes to family and freedom.”

Today Dr. Oswalt practices anesthesiology at University Medical Center. He served as a naval physician during the Cold War from 1976 to 1988 and is quick to say, “It is important for people to realize that even in peacetime, the military makes huge personal sacrifices when it comes to family and freedom.”

His first daughter was born in 1983 on the Naval Base Guam while he was at sea as the physician aboard the submarine, the USS Proteus. Not only did he miss holding his wife’s hand during their first child’s birth, but his daughter was two months old before he ever got to hold her.

An interesting thing about naval doctors—in order to appreciate and fully understand the injuries you might be treating, you get to go through the same training as the men who will likely be your patients at some point. Hence, a doctor who will be treating deep-sea divers undergoes deep-sea diving training as though that is his job.

His charge was the responsibility for the health of his crew aboard the submarine. There were approximately 1,000 men looking to him to do his job well at every hour of the day and night. He also had to understand everything about the workings of the submarine and the unique challenges that confronted men who live there for months on end.

Dr. Oswalt considers that a high privilege and says, “I loved everything about it. The Navy allowed me to grow up, to mature, and to decide what I really wanted to do for the rest of my life.”

The Telling Project has given him a platform to speak about the challenges as well as the privilege that came with military service. Regardless of rank or branch of service, military personnel face the hurdle of transitioning from civilian life to military life in the beginning, and an even bigger challenge to transition back from military life to civilian life at the end of their service. Both events are tremendous adjustments—physically and emotionally.

One thing he most appreciates about The Telling Project is the fact that those who tell their stories come from different eras in America’s history, but their stories, their appreciation for our way of life, and how they feel about their service meshes perfectly together. And it is beautiful.

And FYI, his youngest daughter, a graduate of Virginia Tech, designs submarines as a Naval architect. How great is that?

William Mabry Mayfield as told by Peggy Mayfield Gouras

Peggy grew up in Shreveport, a baby boomer who enjoyed the freedoms and wonder of being American post World War II. As a child, she used to accompany her grandmother to the local cemetery where her grandmother “tended” the grave for her youngest son, Mabry Mayfield, who had been killed in action in Belgium in November 1944. Peggy always noticed the inscription, “Resting place known only to God.” His body had never been found.

Her grandmother explained that she thought Mabry was in the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia. Peggy just accepted the mystery about the uncle she never got to know, but when her own father, John Hulvatus Mayfield, also a WWII veteran, passed away in 2004, she discovered amid his belongings a typewriter case filled with letters. Here was the story of his younger brother Mabry and their mother’s tenacious effort to find her son and bring his body home to the family plot in Shreveport.

Before the age of email and texting, “snail” mail was the only communication families had with their servicemen. A letter Peggy’s grandmother and grandfather had mailed to Mabry in October, 1944 was returned mid November with the word “Deceased” written on it, then a line drawn through that horrible word and the word, “Missing” written above it. This was the first inkling the Mayfields received that something was wrong.

What happened next was a fierce campaign of letter writing waged by a mother who was determined to find her boy. She wrote to the White House. She wrote to Mabry’s friends, his commanding officers, and every living breathing soul who might give her a reason to hope. Several months passed before Mrs. Mayfield heard the confirmation of her greatest fears—her boy would not be coming home. He had been killed on November 7, 1944, by an 88 mm shell that made a direct hit on his foxhole.

Peggy pored over these letters and was so moved by them—the esprit de corps in the replies from Mabry’s friends, the dignity and compassion expressed by those in high places, the regard that everyone held for Mabry—that she, a retired second grade teacher in Vicksburg, caught the passion of her grandmother. She decided to continue the journey of finding Mabry.

In The Telling Project, she recounts her own journey that led her to connect with the remaining few of Mabry’s 104th Division, the Timberwolves. She made two trips to Belgium in pursuit of Mabry’s final resting place and finally found his very name on the Wall of Remembrance in a cemetery in Margraten, Belgium—but not before a number of remarkable coincidences, meetings, relationships with Mabry’s friends, and an education in love for America that she might never have had but for her uncle’s legacy.

The Wall of Remembrance at Margraten contains the names of 1,700 soldiers. They were husbands, fathers, sons, and uncles, and they were all so very young. Peggy’s part in The Telling Project will move you to tears, but her discovery of the gratitude of the Dutch people for what the Americans did for them in WWII was one of the best parts of her story.

One of the many Dutch friends she made along this quest for her uncle’s final resting place wrote to her, “It was my deep honor to accompany you to Margraten Cemetery to find your uncle. What your uncle did for my parents and grandparents was more than we can ever repay you. He gave his life for our freedom so that my kids and I can grow up in peace and do what we want. It was my deep honor.”

Thomas C. Rollins

Ridgeland attorney T.C. Rollins joined the Marines in 2002 while a student at Mississippi State University. He served in the reserves and was deployed to Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2004 where his task involved convoy security. His base was located near Fallujah and his unit would escort military and civilians as far east as Baghdad and as far west as the Jordan border.

Ridgeland attorney T.C. Rollins joined the Marines in 2002 while a student at Mississippi State University. He served in the reserves and was deployed to Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2004 where his task involved convoy security. His base was located near Fallujah and his unit would escort military and civilians as far east as Baghdad and as far west as the Jordan border.

He explains, “I was a turret machine gunner during the convoys, and I was critically injured when my Humvee rolled over while on a mission.” That injury resulted in a medical retirement, and he continues to have pain in his hip and knee and intermittent swelling of his leg although he says, “I get around fine. The military doctors did a good job putting me back together.”

The Telling Project “gives us the opportunity to give the public a glimpse into the wide range of experiences that veterans face. As he says, “Joining the military is like writing a blank check. You have to go when ordered regardless of whether the mission is worthwhile. I did not protect America’s freedom in the same sense that the World War II veterans did.

“I am proud of my military service and think that it is a worthwhile pursuit for those who feel the call. I was anticipating making a career in the military prior to my medical retirement.”

He believes the Iraq War possibly caused an increase in terrorist activity. “Many people think the Vietnam War was unjustified. However, that does not diminish the sacrifices that those veterans made.”

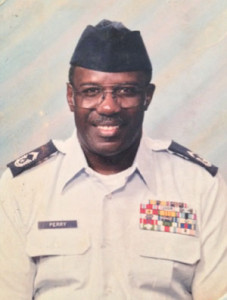

Lee Perry

Brandon resident Lee Perry grew up in Canton. The 71 year old well remembers the day he was chopping cotton as a seven year old and looked overhead to see the first airplane he had ever seen. It was flying at treetop level; the door was open, and a man standing in the door waved to the little boy below. He decided that very day that he wanted to know everything there was to know about airplanes.

Brandon resident Lee Perry grew up in Canton. The 71 year old well remembers the day he was chopping cotton as a seven year old and looked overhead to see the first airplane he had ever seen. It was flying at treetop level; the door was open, and a man standing in the door waved to the little boy below. He decided that very day that he wanted to know everything there was to know about airplanes.

When he graduated from high school in 1962, he joined the Air Force and as he says, “I never looked back.” He served two tours in Vietnam between August 1965 and June 1967. His job was as an aircraft mechanic, and he was quite good at keeping the planes flying, fixing their problems, and turning them around quickly when they needed repair. He was proud of the work he did.

“By the grace of God, I made it through Vietnam. There is no such thing as ‘luck’ on the battlefield. It’s a blessing. It is God’s grace.”

When he came home, he was quickly hit in the face with reality. The unpopular war meant that those who had served in the military were not welcomed as heroes who had protected the freedoms Americans hold dear. They were ostracized, spit on, called names, and when they applied for jobs, they were either sent to the back of the line or rejected outright. It was a devastating situation, but Ed was remarkably resilient. And he still believed in his country.

After he was discharged from the Air Force, he joined the Air National Guard and continued to work on planes from January 1972 to 1999 when he retired as a Master Sergeant. When 9/11 happened, he says he “was still on the list’ and thought he might be called up should there have been a shortage of his position—ace aircraft maintainer. “I would have gone willingly,” he says.

Today he serves as the State Commander for the VFW, “because I don’t want another soldier to come home and be treated bad the way we were after Vietnam.” He is somewhat a mentor to the younger men telling them, “When you get over there, think of one thing and one thing only—survival. You come back here and I’ll walk with you and help you wherever you want to go. If I have to pick up your casket, I can’t help you.”

“People who haven’t been in war do not know what it is. You can’t go and not be changed.” But like he says, he is one of the blessed. His scars have not been as debilitating as many of his cohorts’.

The sacrifices are enormous, Lee explains. The families left behind, the time not spent together, the sense of imminent danger, and the sheer 24/7-vigilance that the military commands—all take their toll in some way.

Still, he is one who is proud of his service and says to younger men today, “The quickest way out of the ghetto is to join the military.” He sees his experience as something that made him a genuinely better person.

He is an honorable man who says, “The price of freedom is paid with the ultimate sacrifice of a soldier’s blood.”

Like a Korean War vet aptly put it, “All gave some. Some gave all.”

God bless America.