By KATIE EUBANKS

Sean Milner

He grew up at a children’s home —

and now he runs it

Sean Milner remembers the gunshot from when Oma wounded herself in the shoulder.

“(My siblings and I) ran out on the back porch and brought her back in the house,” Sean says. “My older brother Bruce, who was 8, ran two miles to the nearest house that had a phone.”

It was 1969, and Sean was 5 years old.

That incident led to his first stay with the Baptist Children’s Village.

His father, Johnny, had a commendable military record — World War II, Korea — but he was no friend of the law. He’d serve time in one state and then move his family to another state. The Milner siblings were born as far apart as Pensacola, Florida, and Sacramento, California.

The day Sean was born, Johnny wasn’t there, which is why Oma refused to pronounce Sean’s name “Shawn,” like his dad wanted. Instead, it’s pronounced like “seen.”

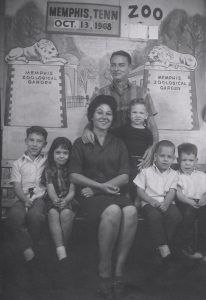

The Milner family at the Memphis Zoo before the kids went back to Baptist Children’s Village. From left, Bruce, Kim, Oma, Johnny, James (Booboo) in Johnny’s arm, Mike and Sean.

When Sean was 3, Johnny Milner left his wife and five children in Sacramento. “He took us all to a park, set our mother on a park bench, left to get lunch and never came back. The youngest was 5 days old,” Sean says.

Oma managed to get the family to her home in Claiborne County, Mississippi. But she was a “bad alcoholic,” Sean says, and unable to handle all that life threw at her.

After Oma shot herself, the oldest four Milner kids went to Baptist Children’s Village, while the youngest, who was too young to leave their mother, lived at home.

When Sean was 8, his father showed up. Johnny and Oma reconciled, and the Milner kids went back home.

It didn’t take.

“(Our parents) owned bars around Jackson. We wound up living in a trailer behind one of (the bars), on North State Street — I think it was called the Starlight Lounge,” Sean says. “We rarely went to school.”

The Starlight was a honky-tonk. The Milner kids would wait until the music got going — “we joke that when we heard George Jones, we knew the time was right,” Sean says — and sneak in the back. “We’d play pool with some of the drunks until Mom caught us. That was fun.”

One night, Oma bashed in the Starlight windows with a crowbar. “She’d caught dad with a woman or something,” Sean says. And eight months after leaving Baptist Children’s Village, the Milner kids went back — all five of them this time. Sean was still 8, the same age he’d been when they left.

Running away

Sean compares the cottages on BCV’s Jackson campus to a “big subdivision” and says he and his friends were “mischievous” like any other boys. His childhood wasn’t perfect, but it was fun.

What he didn’t know then, and didn’t find out until he was 40, was that his mother would visit sometimes.

“She would get drunk, pull onto the campus and want to confess all sins. The staff would drive her home, put her in bed and leave.”

Meanwhile, Sean and his buddies had a big time.

How big?

One night when Sean was 9, a man named Henry Glaze and his wife came to serve as relief for the houseparents at Sean’s cottage. Henry was a Jackson police officer.

“That night, five of us ran away,” Sean says.

Now, there are two versions of this story: In Sean’s version, the boys never left Jackson. But his friend, the late Tommy Wayne Crow (who made sure to tell folks he was named after John Wayne), said they made it to Florida. “It was like a fish story,” Sean says.

At any rate, the boys got an idea, as they often did. “And whatever the idea was, that became the plan. (And) for some reason, going to Pearl and mowing grass for a living became the plan.”

Only problem was, it was November, and the boys wound up sleeping on the side of the highway. Tommy Wayne was shivering. So he and Sean decided to go back.

They made their way to a Burger King, which had a payphone.

Tommy was chubby and “a cute kid,” Sean says. “So I told him, ‘Tommy, go ask those people for a dime.’ And he came back with a dime.”

After a bit of puzzling, Sean directed his friend again: “Tommy, go ask those people how to call the police.”

The police came. The Burger King manager gave the kids free food.

Back, from left: Kim, Bruce, Mike and Sean Milner. In front is James, aka Booboo.

“We ate, and we were feeling good now,” Sean says. So they decided to make a break for it.

“We went out the front door, and these two meaty paws came down on our shoulders. ‘Y’all going somewhere?’ (We said,) ‘Yeah, we was gonna go outside and wait for you.’”

The officer phoned Henry — the houseparent who was also a cop — and acted like he wanted to take the boys to the “DC,” or detention center. Sean, refusing to break, just stared at the officer like a hardened criminal. In the end, it didn’t matter: Henry came and got the boys.

“They always came and got me,” Sean says. Yes, he ran more than once.

“I had to rake leaves for a week when I got back. They didn’t roll out the red carpet for me. But it was a picture of Christ and how He pursues us.”

Coming full circle

After the split from Johnny Milner, Oma started living with a man named Travis Dukes, who owned a Shipley Do-Nuts in Jackson.

One weekend a month, Sean and his siblings got to stay at their mother’s apartment. Sean grew up making donuts for Travis, whom everyone knew as Pop. Pop and Oma never married.

It wasn’t ideal, but it was a family — and Sean learned that family was important.

When Sean was young, he didn’t believe in God. He thought that if God was all-knowing and all-powerful — and truly loved him — then he wouldn’t have to live at BCV.

But when he was a preteen, a houseparent led him to Christ. He was baptized at First Baptist Jackson, where his cottage attended church. And when he was a teenager, he started taking his faith more seriously and putting his rebellious days behind him.

Just before his sophomore year of high school, he got the opportunity to live at the BCV home in New Albany. Unlike the Jackson campus tucked away in the woods, this home was right in the middle of New Albany.

“You found your own way to school. You were very much a normal kid,” Sean says.

“At first I hated it. I wanted to come back to Jackson.”

But one of the houseparents, known as Papa J., told Sean to stay till Christmas. “He said, ‘Sean, you’re institutionalized. You’ve got to learn to act for yourself and think for yourself.’”

By the time Christmas rolled around? “You couldn’t have drug me away,” Sean says.

After graduating high school in New Albany, Sean attended Mississippi College — he lived on campus during the school year and at BCV the rest of the time. When he left BCV after graduating, he held the record for the longest stay.

“I hold the record over my brother Mike by one year, and he hates it. But I flunked third and seventh grade (and had to repeat them), so that’s why I hold the record. He likes to make sure and tell people that.”

Sean (back) with his wife, Elizabeth (center), son Nathaniel and daughter Rebecca.

After college, Sean worked as an insurance claim rep in Tupelo. “I hated that job, and it hated me,” he says, marveling that the company kept him for two years.

But during that time, he married his wife, the former Elizabeth McFadden. After getting married, they moved back to the Jackson area so he could attend Mississippi College School of Law.

Sean practiced law at Milner Nixon for 23 years. He and Elizabeth have two children: Nathaniel, who graduates from Mississippi College this month, and Rebecca, who’s now a mental health therapist in Colorado.

A few years ago, Sean had lunch with Rory Lee, executive director of Baptist Children’s Village at the time. Dr. Lee said he was about to retire, and asked Sean what he wanted to tell the board about “his availability.”

“There was no way I could turn it down,” Sean says. He’s been executive director for two and a half years now.

“Some of my houseparents were still alive when I became executive director, and they were stunned. Not impressed — stunned. Like, ‘This kid’s not in jail?’”

Wouldn’t trade it

Sean’s mother was a believer, he says. She just never could give up alcohol. He and Oma had conversations about faith. And he loved her — Baptist Children’s Village taught him to love her — even though she “embarrassed the fool out of me,” he says.

He never heard from his father after returning to BCV the second time, but research revealed Johnny Milner lived until 2015. Oma died when Sean was a sophomore in college.

Sean’s brother James, the youngest Milner sibling, got involved with the wrong people after leaving BCV and was killed in Georgia in 1992.

Life hasn’t turned out perfect in every way, but BCV provided Sean and his brothers and sister with the secure foundation they wouldn’t otherwise have had.

“I wouldn’t trade my childhood for anything.”

Providing a solution

Although the Milners never rejoined their parents, BCV’s goal is to reunite families whenever possible.

He gives an example: One day a BCV houseparent was at the grocery store with the kids from her cottage. She saw a woman crying in a car, and she had a child with her. The houseparent drug her BCV kids over to the vehicle and asked the woman, “Can I help you?”

“No, you can’t help me,” the woman said. “All I have is this car, my husband left, and I just ran out of gas.”

Within two hours, Sean says, “(the mother) came to see our campus — and we have beautiful campuses — saw the house, left the kids, and we had that family for about 18 months. The mom got back on her feet, and we put the family back together.”

Today, BCV has seven homes across the state. The agency sold its Jackson campus and moved to a statewide model, so hopefully, most children can stay at a home near their parents.

BCV homes — and they are houses, not apartments or “facilities” — are located in Independence (near Coldwater), Water Valley, Louisville, Star, Brookhaven, Waynesboro and Wiggins. The kids attend church, school and extracurricular activities.

BCV still makes arrangements with certain families to let their children stay with them on weekends — sometimes every weekend during the summer, Sean says. But the agency has to see the house and make sure it’s a safe situation. “No way am I letting a child go home to an unsafe environment.”

While most kids come to BCV via private referral, the agency is also licensed through Child Protective Services — because “(the state takes) kids who may need to hear the gospel,” Sean says.

Sean Milner (back row, second from right) with family.

Normally, when the state places a child with an agency, that agency gets some money as well. But the BCV tells the state to keep the check. Why?

“There are two reasons: 1) We’ll never subordinate the gospel, and 2) God didn’t tell the state to take care of children — He told us.”

Sean says the BCV houseparents are “heroes” and notes that they don’t work in shifts. They’re at the cottages long term (though they do get occasional relief from people like Henry Glaze, who retrieved Sean and Tommy Wayne from the Burger King).

“For however long the child is there, we want to teach them about a Christian family.”

While BCV is not a therapeutic home, the agency does use trauma-informed care, and houseparents are trained to understand where the kids are in terms of brain development.

Most importantly, the houseparents provide emotional and spiritual support.

“If a kid is upset (because) they’ve been turned down (for adoption) four times, and they think nobody loves them, the houseparent is the one who sits on the bed with them and tells them, ‘No, the Creator of the whole universe loves you so much, He sent His Son to die for you.’”

BCV’s Dorcas In-Home Family Support Program aims to help families before they become disrupted. In 33 counties in the Delta and north Mississippi, “case managers go into the home when families start getting in trouble … We teach parenting, cooking. We meet the family where they are,” Sean says.

Between the Dorcas program and the residential program, BCV serves approximately 60 to 65 kids at any given time, and around 200 per year.

Sean notes that outside of the gospel, there’s not just one solution for kids and families. “We need good foster parents. We need residential children’s care. We need adoption.”

For Sean, the solution was Baptist Children’s Village.

People sometimes ask him, “Was it really God’s plan for you to have to live at a children’s village?”

Sean could answer in theological terms.

“There are answers to that,” he acknowledges. But the bottom line?

“If I hadn’t been there, I wouldn’t be here.”