By KATIE EUBANKS

Clockwise from top left: Stacey, Benjamin, Matt, Sofia, Nora and Lily Ayars on Easter Sunday 2020, shortly after moving to Ridgeland after 13 years in Acul-du-Nord, Haiti.

Matt and Stacey Ayars

How God brought them from Haiti to Mississippi

Imagine accepting a job in a foreign culture in another country, preparing to move in a couple months — and then suddenly being told you no longer have months, but hours. You have to move tomorrow.

That’s what happened to Matt and Stacey Ayars and their four children as the COVID-19 pandemic hit in spring 2020.

The “foreign” culture they were about to enter? Ridgeland, Mississippi.

The beloved home they were leaving after 13 years? Haiti.

To be fair, Mississippi isn’t “foreign” to Matt and Stacey in the traditional sense. After all, they are American. She’s from Columbus, Ohio, he’s from New Jersey, and they met at Asbury University in Wilmore, Kentucky.

But before arriving in the Magnolia State, they spent about a third of their lives in Haiti. They moved there as soon as they could get married, grab their degrees and launch out. Haiti is where they raised their kids and made friends.

And it’s where they learned the value of community — the fact that “it’s never about a project or program or budget. It’s about the personal relationships,” says Matt, president of Wesley Biblical Seminary in Ridgeland.

That’s a lesson he and Stacey never want to forget as they continue following God’s call in Mississippi.

A five-year commitment

While Matt and Stacey were dating, she felt a call to work in full-time missions, and he felt led to preach God’s Word. So they got married right after their junior year “because we wanted to go to the mission field as soon as we could,” Matt says.

They found the perfect opportunity that fit their skill sets: Emmaus University, in Acul-du- Nord, Haiti, was “desperate for Bible teachers and needed a marketing director,” Stacey says. Matt could teach, and she had a photojournalism degree. Plus, she had already worked in Haiti. They moved to Acul-du-Nord in 2007.

“We committed to five years,” Stacey says.

“We thought we’d not have kids for five years, and just pour ourselves out.”

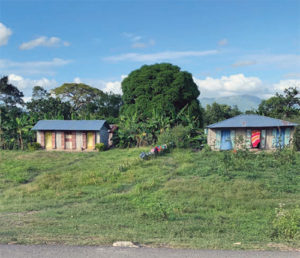

The market where the Ayars family bought produce in Haiti.

A higher quality of life

“For me, compared to our culture, it’s exotic,” Matt says.

“It’s super hot, super dusty, super poor. It’s mountainous. You’re a minority everywhere. You’re adapting to new cultural norms — and the burden of being a teacher.”

There were no paved roads, no convenience stores, and minimal electricity where Matt and Stacey lived. They take turns rattling off the challenges they dealt with: Getting a fan to work. Not getting malaria. Teaching biblical Hebrew to non-native English speakers. (Insert panicked laughter here.)

“I was still trying to figure out how to cook anyway, how to be married,” Stacey says. “And (Matt was) trying to deal with electricity and water.”

There was no city water, so they had to pump their own. For electricity, they had diesel generators at first, and later solar power. The electricity went out at night and wasn’t enough to keep the refrigerator cold. But Matt and Stacey were the only people in their village who had a refrigerator.

Lily Ayars gets a cooking lesson in Haiti.

When asked to describe Haitian food, Stacey says:

“Everything is rice. So rice and beans … some kind of vegetables. Maybe a small amount of meat (usually goat). Because there’s no refrigeration, there’s no dairy. The main meal is lunch, and that’s rice and beans. For dinner it may be a cup of tea.”

The Haitian dish that the Ayars kids still crave today is something that might not sound appetizing: spaghetti for breakfast. “It’s like a garlic and oil spaghetti, with a big glob of mayonnaise and a big glob of ketchup,” Stacey says.

Sometimes folks would put spaghetti and milk in a blender and drink it like a smoothie — warm, remember, because no refrigeration. It’s actually good, Stacey and Matt say, and is sort of like Cream of Wheat.

When they weren’t navigating a new menu, to get in touch with family due to poor internet. But as with the fridge, “nobody else even had a laptop. It was humbling,” Stacey says.

“When we first got there and we didn’t have friends and family, that first year was rough. But after we (found community), all those other (convenience) things became secondary.”

Matt says simply, “Their standard of living is low, but their quality of life is high.”

In April, Stacey and the kids visited Pastor Enick and his family. Enick has been friends with Matt and Stacey since they first moved to Haiti.

Not just a job

Two years into their time in Haiti, Matt and Stacey welcomed their oldest daughter, Lily. So what happened to not having kids for five years?

“I think we realized we weren’t doing a job,” Stacey says. “(Haiti) was our life.”

Secondly, “(the work) was never done,” she says. The things they thought they’d accomplish in Haiti in five years? No way. They stayed for 13. “It took us years to even get to a place with people where they trusted us,” Stacey says.

Lily, now 12, was followed by Sofia, 10; Nora, 5; and Benjamin, 2.

While the family thrived, especially the kids, Stacey and Matt did struggle with some parts of their lives in Haiti, beyond the lack of first-world amenities.

Matt, an introvert, was “used to being able to just go to Barnes & Noble or take a drive” to have some time alone, he says. But there is no “alone time” in the Haitian culture, and there was no place to get away to. Instead, he found solace playing guitar.

Stacey missed her family. “While we were there having our babies, my sister was here (in America) having her babies. But I got to be an aunt to plenty of kiddos there.”

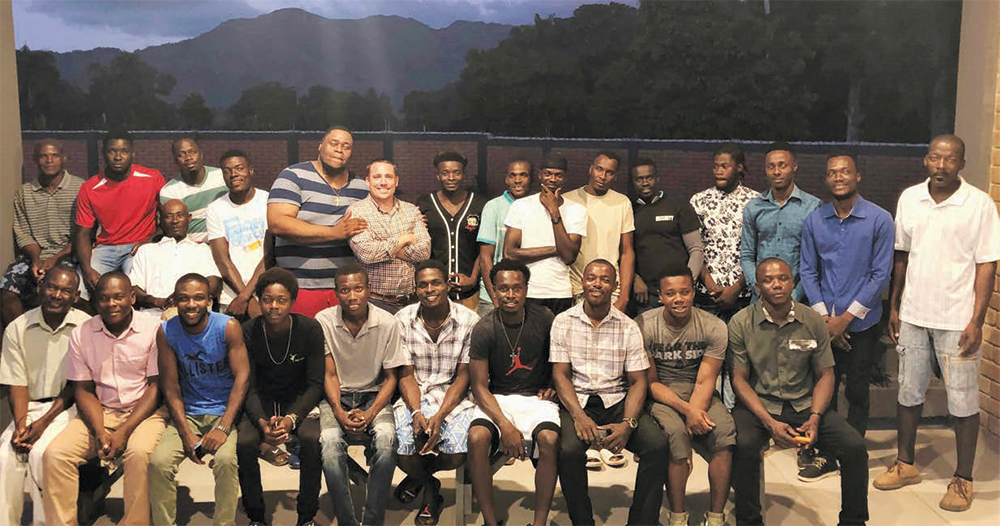

Matt led a weekly men’s Bible study in Acul-du-Nord for years.

New calling, new adjustments

From 2008 to 2012, Matt and several Haitian friends took online courses at Wesley Biblical Seminary. Once a year, he traveled to the metro Jackson campus for a three-week intensive.

Then in 2019, WBS President John Neihof suddenly passed away.

“They reached out to me (to apply for the position),” Matt says. He said no at first — more than once —but then, “not thinking we’d ever get it in a million years, and at the counsel of some trusted friends, I sent in the paperwork.”

When he was offered the position, “we sensed God saying yes,” he says.

“We shared with the (Emmaus) school board in February that we felt the Lord calling us here,” Stacey says. Then on March 25, they got a call from their mission organization, One Mission Society, saying they had to leave Haiti the next day due to COVID-19.

By that time, Matt was president of Emmaus University. He was leaving in the middle of his final semester in that role.

“We thought we’d be going back (to Haiti) in two weeks,” Stacey says. Instead, she and Matt slowly adjusted to life in metro Jackson — a place they’d never lived before — in the middle of a pandemic.

“I didn’t know one person,” Stacey says.

“I was here in community with my coworkers (at WBS) every day,” Matt says. “She’s at home with the kids homeschooling. It was Haiti all over again: new place, exotic culture.”

At times, Stacey says, it was hard to make sense of awkward interactions: “‘What if this is COVID? What if this is Mississippi and the South? What if this is this person’s personality?’

I felt very lost for a while.

“I wouldn’t want to do that part again, ever,” she says. “But you look back now and go, ‘OK, the Lord was here, and He was doing this.’”

The kids have had to adjust, too, and not just because of COVID.

Sofia Ayars with classmates in Haiti.

“In Haiti, we lived on a seven, eight-acre walled campus,” Matt says. “It was summer every day. They had full reign … to go to the kitchen and help make blended spaghetti, or help butcher the goat. Here, it’s like, you can go play in this tiny little backyard, but not out front because there’s traffic.”

“And I have to be able to see you at all times,” Stacey says.

In addition, “(our kids) know how to make friends in Haiti,” Stacey says. “It’s a totally different culture here.”

For instance, Haitian kids are more likely to welcome a stranger than American kids are. The Ayars children have had to initiate a lot of friendships here. But they’ve done it.

“They’re very comfortable in their skin,” Stacey says. “They can talk to anybody.”

That comes from living in Haiti, where neighbors spend quality time together and you’re never alone. That sense of community is one of the main things the Ayars family is determined to keep with them in their new home.

The Ayars kids with Haitian family.

‘People are people’

In Haiti, if people found out you were sick, “you knew the next day there’d be a line at your door,” Stacey says.

That kind of direct, personal support doesn’t always happen naturally in America’s individualistic culture. But every Sunday night in Ridgeland, the Ayars family has dinner with their neighbors.

“It’s our favorite night of the week,” Stacey says. “We (also) take lots of walks so we can be visible and suck people into being our friend.”

In Haiti, the kids went three days a week to the Haitian school, and spent three days a week homeschooling. The latter was unheard-of in Haiti since many mothers don’t have the education to teach their kids.

But in metro Jackson, homeschooling is pretty common, especially after COVID.

“I was really shocked that all kinds of people homeschool here,” Stacey says. On Fridays the kids attend an enrichment program with other local homeschoolers, so their siblings aren’t their only classmates.

The family has also been able to find a church, after visiting “tons and tons” of different ones, Stacey says. They’ve settled in at Foundry Church in Flowood, where most of the congregation are twentysomethings.

Thanksgiving 2020 in Ridgeland.

One night at a church function, Stacey made a self-deprecating joke about being older and “not cool” compared to their young friends, and one of those friends replied, “Did it ever occur to you that that’s exactly what we wanted?” Point taken. In fact, that’s part of why Matt and Stacey felt led to Foundry.

“We wanted to go where we were most needed,” Matt says.

Stacey still works remotely as marketing director for Emmaus, and will visit in person once a semester. In April, she spent two weeks there with the kids, who ate their weight in spaghetti for breakfast.

Matt still teaches a three-week intensive at Emmaus once a year. Meanwhile, he’s excited about where WBS is going. “We’ve got a really healthy culture, we have more students than we’ve ever had, financially we’re in good shape, and we’re the most racially diverse seminary in the nation,” he says.

He and Stacey both have found the next step of their calling. They always said they’d go wherever God sent them — whether Haiti, Mississippi, or anywhere else.

And in the end, living on mission doesn’t change as much from country to country as we might assume, Matt says. “People are people are people.”