By KATIE EUBANKS

Jackson Police Chief James E. Davis

Learning to hear from God

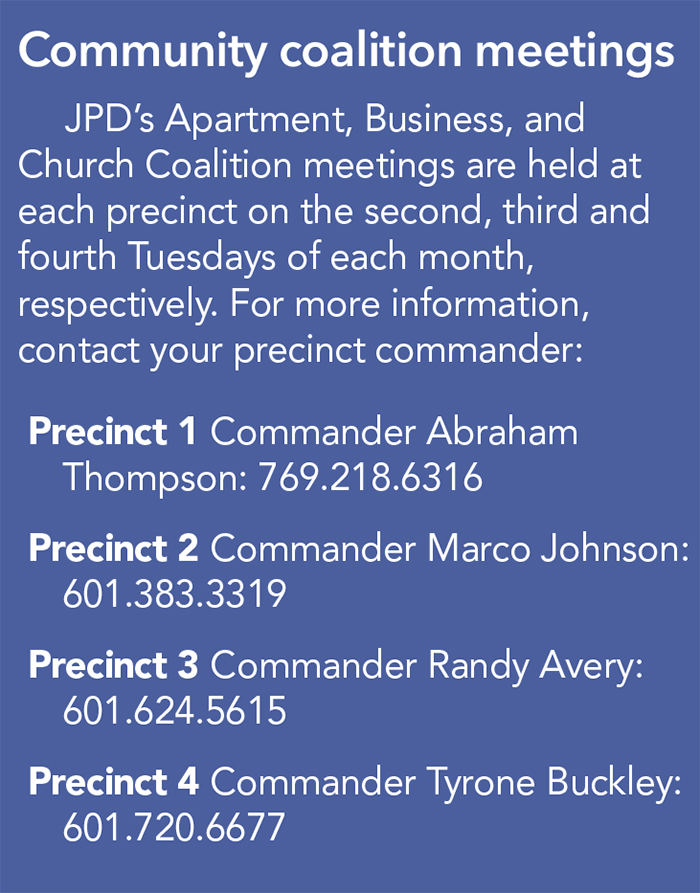

When you walk into Jackson Police Chief James E. Davis’ office, you’re immediately drawn to the open Bible on the windowsill. The window offers Davis a daily view of the city he serves.

Anybody can say he starts his day reading that Bible and praying, as Chief Davis does.

But the more you hear from him, the more you realize he’s a man who seeks to hear from God.

That’s a skill he’s had to learn over the years — and one he desperately needs in his job.

Chief Davis starts his day reading this Bible in his office and praying over Mississippi’s capitol city.

From the ranch to the academy

James Davis, 52, was born the third of eight children in Natchez. He learned hard work, respect and integrity, both from his natural parents — Gloria Davis and the late James Young — and a second set of parents in Natchez.

When James was 9 years old, he and his brother Curtis started working summers and after school at a cutting horse ranch owned by the late Phil Vasser. Phil and his wife, Jimmi Lou, never had children of their own. So, in addition to breaking horses, feeding cattle, cutting grass and building fences, James and Curtis attended Vasser family cookouts and became like sons to Phil and Jimmi Lou.

The future Chief Davis training as a JPD SWAT officer.

Chief Davis’ mother encouraged the relationship, he said.

“At the ranch I learned if it’s hard, just pray more, have faith, and believe you’re going to get through.”

From Natchez he moved to Jackson, where he worked as a hall monitor and then an in-school suspension coordinator at Murrah High School. One of the teachers, who was married to a police officer, suggested he go through the JPD Training Academy.

“So I went through basic training. We were trained really, really well. And I became a patrolman.”

That’s when he had to start praying more.

His first call

When Chief Davis first became a patrol officer in the early ‘90s, he worked the midnight shift, from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. His first solo ride was one that ultimately sharpened his focus on God and His Word.

“I was so excited to be solo,” he said. “Now I’m not being babysat (as a recruit) anymore. Now ‘I’ve got this.’ I came to work at 10 (p.m.), I got out of roll call, and I said I’m 10–8, which means I’m in service.”

While patrolling, he received his first call: Shots fired.

“When I got on the scene, I saw that it was a homicide. A teenage girl had been shot. That was the first time I had seen a deceased person. I had to put my training together really, really quick,” he said.

“I did a lot of praying to try to understand, how could someone take someone’s life? I lost a lot of sleep.”

The homicide turned out to be an accident. Still, he was shaken up. He found comfort in prayer and scripture.

“The Bible says God will give you wisdom. I read about the wisdom of Solomon. … And I started understanding the importance of (police) work,” he said. “I believe it’s doing God’s work.”

Mr. Mississippi and ‘spiritual fitness’

As strange as it may sound, another thing that led Chief Davis closer to God was bodybuilding.

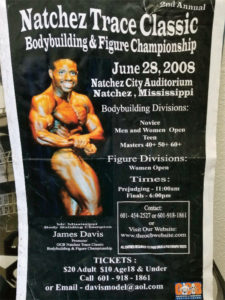

A photo of Chief Davis from his bodybuilding days draws attention to a flyer for the 2008 Natchez Trace Classic, a bodybuilding event he promoted. He plans to go back to promoting bodybuilding after he retires.

Push-ups and sit-ups came naturally to him at the police academy. Then a former officer who had competed in bodybuilding challenged him to do the same. Davis trained and competed from 1995 to 2008, and he won Mr. Mississippi in 1998.

“More people knew me from bodybuilding than as an officer, because I was on the midnight shift (for a time),” he said.

He also trained private fitness clients on the side. The following is an approximation of his summer schedule during his bodybuilding years:

• 10 p.m.–6 a.m.: Work JPD shift

• Morning: Train fitness clients

• Afternoon: Sleep a few hours

• 5–7 p.m.: Work out

• Evening: Sleep a couple hours, then go back to work and start all over.

“When you’re training and working, (God is) all you have. It’s like fasting,” he said. “If you’re depriving your body of good food that you love eating, and you’re depriving yourself of sleep … it takes a lot of spiritual discipline.

“I looked forward to the summer because it brought me closer to God.”

Even in the off season, if he needed spiritual strength or wisdom, “I would go into bodybuilder mode, and I would fast and pray. And I would get the answer.”

When he retires, he plans to promote bodybuilding again, he said. “I call it spiritual fitness.”

‘We cannot put everyone in jail’

Chief Davis never imagined he would be chief. He did join SWAT and became the range master at the academy. But he was planning to retire once he hit 25 years. Then in 2009 he took the sergeant’s exam, and “God kept promoting me,” he said, until Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba appointed him chief in 2018.

“Now I really have to pray more, because I’m dealing with a lot more citizens, churches, business owners, schools, and the community,” he said.

“People often ask me about (my cross pin), and I get an opportunity to tell them about Jesus,” Chief Davis said. “He died for all our sins; none is perfect. If we just confess our sins, He is our Redeemer.”

“My prayer when the mayor offered me the job was for the Spirit of God to hover and soften the hearts of people with bad intentions, and to comfort the people crying out (for justice). That is still my prayer.”

Late last year, a multi-agency task force called Targeting Gun Violence was formed in response to a rash of shooting deaths in Jackson, which saw 82 homicides in 2019 — nearly equaling the 84 that occurred in 2018, the highest number in more than 20 years. The task force resulted in dozens of arrests on charges including murder, aggravated assault and armed robbery. But more work is needed.

Chief Davis has asked the Jackson City Council for desperately needed funding — both to hire additional officers and to pay existing officers more.

JPD did receive some funding in the form of a “hot spot” grant, to install a couple dozen cameras in residential and commercial areas in south Jackson, and the impact has been positive so far, Chief Davis said. He hopes to sprinkle such cameras throughout the city as funding becomes available. “We went to New Orleans and Chicago and (LAPD), and cameras made a big decrease in their crime.”

But the biggest tool JPD has, he said, is service. Chief Davis believes the more an officer interacts with people on his or her beat, the less enforcement will be needed. “And (those interactions do) so much therapy for the officers, because it reminds them (why they do the job).”

He learned this from personal experience. In the mid-’90s, he saw a teen boy walking the streets around 3 a.m. Davis gave the young man a ride, got him some food (it was Davis’ “lunchtime”), took him home — and listened to him and his mother hash out some problems.

He learned this from personal experience. In the mid-’90s, he saw a teen boy walking the streets around 3 a.m. Davis gave the young man a ride, got him some food (it was Davis’ “lunchtime”), took him home — and listened to him and his mother hash out some problems.

“By the end of it, they were both crying and hugging each other,” Davis said.

About 15 years later, Davis was getting out of his car at a convenience store when a man approached with tears in his eyes.

“He said, ‘You don’t remember me, but I’m that kid you talked to years ago. I’m a grown man now.’ He pulled out his wallet and showed me pictures of his family. He said, ‘Because of you, I finished school.’

“That’s the kind of service I can get behind. That’s when I really, really understood my values as a police officer.

“Don’t get me wrong, we enforce. We’re putting bad people in jail,” he said. Recently, the department used Jackson’s coronavirus quarantine to make 35 felony arrests (and more than 100 others), seize more than 500 pounds of marijuana, confiscate 49 handguns and 11 assault rifles, and recover 60 vehicles and more than $20,000 in cash.

“But the majority of the people that I’ve come across are people that need some direction, some encouraging … We cannot put everyone in jail,” he said.

“We teach and train our officers to listen to people.”

Training, prevention and accountability

People see a lot of ugly things — racism, inhumanity, murder — when they see the video of George Floyd, face down on the ground and handcuffed, crying out for air as Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin keeps his knee on Floyd’s neck for 7 minutes and 46 seconds (initial reports incorrectly said 8:46). Chauvin’s fellow officers on the scene did nothing, and the encounter killed Floyd.

The future Chief Davis, left, with fellow JPD SWAT officers in May 2004.

One of the things Chief Davis sees in that video is a fatal disconnect between the now former officers and the citizens they were supposed to serve. He believes JPD’s monthly in-service trainings, including on topics like sensitivity, decision-making and use of force, are crucial to avoiding such tragedies.

“We tap into the best practices from across the country,” he said.

“I tell a lot of the officers in the academy, if you just stick to your training, you can’t go wrong. When you’re in the academy, you’re stripped down — you’re in there with men and women, black, white, and you learn how to deal with people more so than anything.”

JPD is not immune from accusations of wrongdoing, including recent cases that have resulted in officers being fired, being put on leave pending investigations, and/or resigning.

In February 2019, Mario Clark died at Merit Health Central a few days after being arrested by JPD. His mother claims officers beat and kicked him while he was handcuffed, and after an internal affairs investigation, Chief Davis and Mayor Lumumba fired the arresting officers — only to see them reinstated by the Jackson Civil Service Commission. JPD has appealed the commission’s decision, Davis said.

In another case, JPD officers are accused of using fatally excessive force on January 13, 2019, while detaining George Robinson, who died two days later. All but one of the officers involved have resigned, and that officer remains on administrative leave pending the Hinds County District Attorney’s investigation, Chief Davis said.

Davis couldn’t say much more about the Clark or Robinson cases, but he made it clear in this interview that he doesn’t mind taking swift disciplinary action when officers are found to have done wrong.

Chief Davis believes the more an officer interacts with people on his or her beat, the less enforcement will be needed. “And those interactions do so much therapy for the officers,” he said.

He also noted that recent Black Lives Matter protests in Mississippi have been peaceful, and that his officers “are able to talk about things of the world with our citizens.”

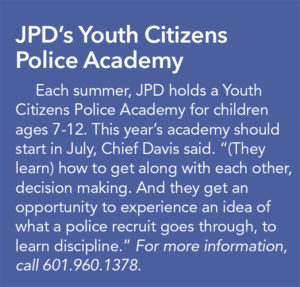

JPD holds regular community meetings in each precinct, where business owners, church leaders, landlords and any other residents can hear and be heard, he said. (See box on page 22.)

When Chief Davis was Precinct 3 commander, he held meetings with managers, custodians and tenants of apartments in his precinct, along with visiting the properties.

“There were broken fences. There were lights out. Some of these apartments didn’t have a curfew. Grass was overgrown, window blinds were broken. … they understood that they had to fix those things to keep their tenants.

“All the while, we were increasing the patrol … So we did our part and they did their part.” Crime went down as a result, he said.

Now he’s taking that model throughout the city.

“The community teaches an officer how to police them — if you as a police officer initiate the engagement.”

‘Police officers are human, too’

Chief Davis also wants officers’ needs to be met, especially their mental, spiritual and emotional needs.

“Police officers are human, too,” he said. After all, he still remembers that first shift, that first dead body. Those kind of memories stick with a person.

“A lot of times, police officers try to internalize so much. They’ve got to deal with their own problems, and the problems of the world.”

Chief Davis serves punch at a luncheon.

Chief Davis said one important resource is the Mississippi Law Enforcement Alliance for Peer Support, or LEAPS, which offers free, confidential peer support from trained law enforcement officers and helps agencies respond to high-stress events. Also, JPD chaplains are always available to talk with officers, he said.

“I want every one of my officers to sit down with a (chaplain) and talk about how they feel,” he said. “If you’re going to be a police officer, you’ve got to have that spiritual foundation. (But) it’s important for officers to see leaders do it. … My meeting with my executive staff starts with a prayer.”

He noted that he himself is accessible to talk with officers as well. But often, they call and encourage him instead, he said.

“And it is always on time. Always on time.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided plenty of opportunities for Chief Davis to support the men and women of JPD, who (as one might imagine) “had questions” when the whole thing started, he said.

“Officers had to take all their clothes off before they went home. I’ve been reaching out to them and their families, making sure we have sanitizers and everything we need.”

Chief Davis has a difficult and perhaps unenviable job, especially in recent months, but he doesn’t complain or act put-upon. Instead, he said, “We have great citizens, and I enjoy meeting their needs.”

And when it comes to meeting the challenges, his default answer never seems to change:

“I find myself having to do a whole lot of praying.”