By Katie Eubanks Ginn

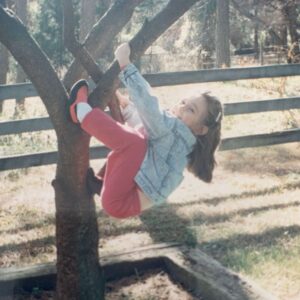

Climbing the plum tree in our backyard in Dardanelle, Arkansas

My first memory of a tree involves climbing one. A plum tree grew in our backyard in Dardanelle, Arkansas, and while the fruit didn’t thrill me, the tree did. I was happier pulling myself up into those branches than I was trying to make friends in my kindergarten class.

I grew faster than the tree did. By the time we were preparing to move to Russellville, the bigger town across the river, I was in second grade, and “climbing” the plum tree accomplished little.

Our Russellville home, the one I grew up in, was bordered by pines — not exactly climbing trees — but I took opportunities where I could: family hikes on Mt. Petit Jean, high-school field trips to Lost Valley State Park. If I saw a tree or a person-sized rock that looked climbable, I was on it.

We moved a couple of times after I graduated high school. Our yard in the Phoenix suburbs consisted of pebbles, and the lemon tree in the back was productive but would barely hold a cat. I contented myself with “climbing” (hiking) to the top of Mt. Humphreys near my first college campus in Flagstaff.

When we moved to Mississippi, our home boasted a bodock tree out front. The bodock provided a challenge, finally, for my gangly 19-year-old limbs: I could climb up to a short height, and then all the hand-holds disappeared. Then it was all about how much nerve you had, either to scoot out onto a certain branch, or to step delicately onto another, at an incline, with nothing to grip onto but air if you fell. Turns out, I didn’t have that much nerve.

I kept climbing in Oxford, sometimes onto the roof of the campus library (OK, all I had to do was step through a window), but mostly metaphorically: I climbed onto the literary magazine staff, into the honors college, into the provost’s office (we attended the same church). All the branches were reachable.

Then, in a British literature class, my hand-holds vanished. Religious debates with classmates left me angry and defensive. By the next semester, I had spiritual vertigo — yet I insisted on continuing to climb. I even chipped away at the very branch that held me, as C.S. Lewis would say, by arguing with God.

I didn’t climb many literal trees that year, though it would’ve done me some good. Instead I sat under the shade of trees and cried while listening to music. I parked my car under the live oak in front of my rental and wept while the Christian duo in the CD player sang, “Can anything satisfy/ When nothing has satisfied?” I sat on a bridge in the woods behind Faulkner’s house and listened to Bono belt out somebody else’s conversion story in “Beautiful Day.” I didn’t climb any trees in those woods. I don’t know if I even looked up.

Eventually, that miserable year became my conversion story. I quit trying to climb my way to intellectual certainty once I realized I’d never get there and didn’t need to.

Some trees are clearly intended for climbers. Others, well … A few weeks ago, Stephen and I were relaxing on a patio in Jackson, and I felt an almost unavoidable desire, at a genetic level, to climb the magnolia next to us. But that tree, a queen even among the pines and live oaks, was not for climbing.

Instead — much like the trees in Eden, or the tree on which God’s Son died, or the Tree of Life in new Jerusalem — she offered shelter and shade to whosoever.

So I didn’t climb. I rested.