By KATIE EUBANKS

Dr. Cathie Phillippi is a married, churchgoing doctor with three kids. But she isn’t perfect.

“I think people see this put-together person … with all the things,” she says. “But I often still kind of feel like a fly on the wall,”like she did as a child visiting her friends’ churches after Saturday-night sleepovers.

As an adolescent, Cathie rejected God — and she certainly didn’t have all the things. She and her single mom “didn’t fit the mold” in the wholesome town of Clinton where Cathie was raised, she recalls.

But eventually, Jesus got hold of Cathie’s heart, and today she is no longer an outsider. She belongs to the family of God.

Rules and turnip greens

Cathie’s parents split when she was 4. She and her mom, Dorothy, moved in with Cathie’s grandmother Wilma when Cathie was 6, just after her grandfather passed away.

“She invited us to come live with her (in Clinton for an) indefinite time,” Cathie says. “At the time, I resented it. … I went from (an unpredictable environment) to rules and turnip greens.

“As I grew up, I realized what a big deal that was — unconditional love, but expectations.”

Cathie learned about Wilma’s upbringing, when marrying young provided a path out of poverty. Wilma had given birth to her first child at 16, worked at a McRae’s department store for more than 25 years, and “she was content,” Cathie says.

Wilma also attended church regularly. Cathie remembers going to services with Dorothy and Wilma, but “I almost felt like a voyeur,” she says. “I didn’t understand it.”

Still, “I was a people pleaser. I wanted to act like I fit in.”

Cathie’s grandmother certainly wanted her to know Christ, but didn’t fret about it, Cathie says.

“I think we feel this pressure to convince someone or draw them in, when really the Holy Spirit has to do the work. With your own children, you want them to come to that understanding as quickly as possible. (But God) does have it.”

Meanwhile, “(My mom) often worked three jobs,” Cathie says. “I was a latchkey kid and always dreamed of what it would be like to have a big family.”

When Dorothy would get a better job, she and Cathie would move out on their own. When things didn’t work out, they’d move back into Wilma’s house.

As a middle-schooler, “a lot of what I felt was anger most of the time — watching other kids have family units that (seemed) healthy,” Cathie says. Her parents had a “volatile” relationship, and she rarely sawher dad.

“I used to spend the night with people on Saturday instead of Friday because I knew they went to church (on Sunday) and there was a tradition about it — (that felt) very warm.

“I studied other families. I went to Catholic church, Baptist church — surveying all different ways of being.”

Drs. Cathie and Mark Philippi, who work at TrustCare Kids and Central Nephrology Clinic respectively, with their kids (from left): Owen, Julia and Madeline.

Hitting rock bottom

After middle school, “I started rebelling on a huge level,” Cathie says. She might’ve enjoyed being a voyeur at church, but now she wanted nothing to do with God.

“Some of that was developmental and puberty. Some of it was undiagnosed anxiety, probably depression, and frustration with things I couldn’t control.”

She’d always been smart, but now her grades started slipping.

“I was searching for value and meaning in anything and everything but God — whether that was trying to be perfect, trying to be popular, drinking and partying, or in relationships with guys. I hated myself,” she says. “I got tired of pretending I was fine — it got exhausting.”

As a ninth-grader, she attempted suicide. “I could not see beyond my feelings,” she says.

By the start of her junior year, she wanted to leave school. After two weeks of 11th grade, she forged Dorothy’s signature on a form that said Cathie was withdrawing.

“(When my mom found out), she had a complete meltdown and said she would go to jail.”

Cathie knew if she had to attend school, it would need to be a place where she could get away from the “bad crowd” she’d started hanging out with. She couldn’t move school districts, so she called Central Hinds Academy and asked to speak with someone in financial aid.

The school put her through to the headmaster, who asked to meet with Cathie and said that if she could pay her tuition in monthly $100 installments until it was paid off, he’d buy her books.

“God was rescuing me from a situation that would’ve ended in my death,” she says.

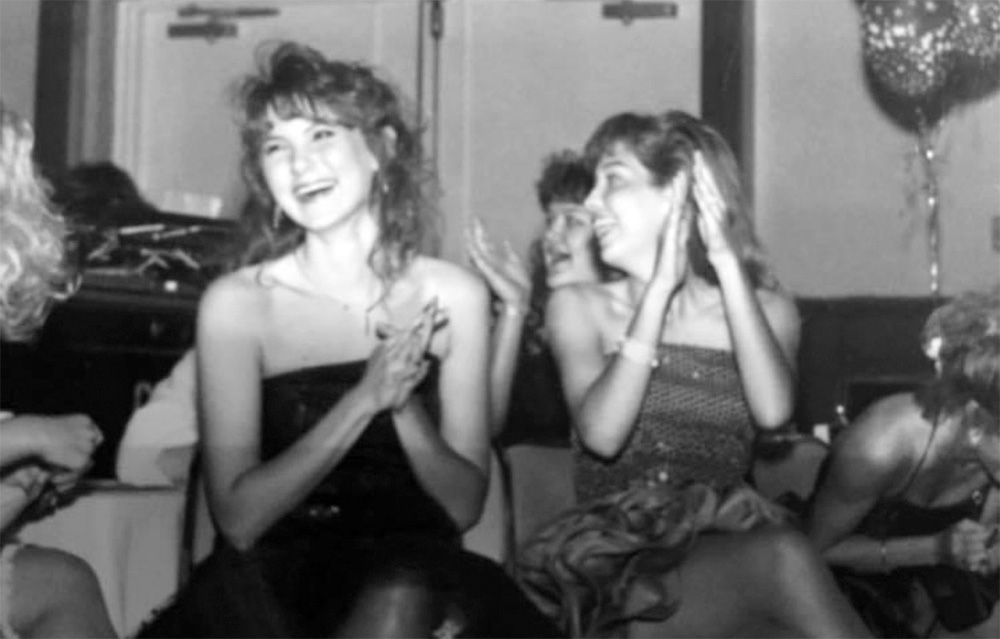

Cathie (left) with friend Jeni Bizot at prom at Central Hinds Academy, where Cathie paid tuition in $100 installments.

At Central Hinds, “the English workbooks had things about the Bible (and) you took a Bible class,” she says. Teachers started pouring into her and telling her she was smart. She joined the yearbook and newspaper staffs. She even played softball.

“I never did know the rules (but) it was really fun!” she says now, laughing.

“Over those two years, that built my self-esteem, and it taught me about God,” she says. “I wasn’t there yet, (but) God was turning my path.”

Then Dorothy cut out a newspaper article about a scholarship being offered by the Rotary Club of Jackson (still offered to this day). She urged Cathie to apply.

“I almost didn’t,” Cathie says. “I’m thinking, ‘I’m not going to get this.’” She wrote the essay and mailed it in, and she got called for an interview. Among a crowd of applicants wearing suits, “I was wearing a dress my grandmother had made, with flowers on it.

“I thought I had made a huge mistake (in applying).”

During the interview, because she just knew she’d never get this scholarship, “I wasn’t trying to impress them … I didn’t think through it.”

She got called back for a second interview. And she got the scholarship.

Thanks to the Rotary club and an additional scholarship from Mississippi College, Cathie attended MC and lived on campus without a huge pile of debt.

More importantly, she found a real relationship with Christ as an undergrad.

“Going to Mississippi College changed my life.”

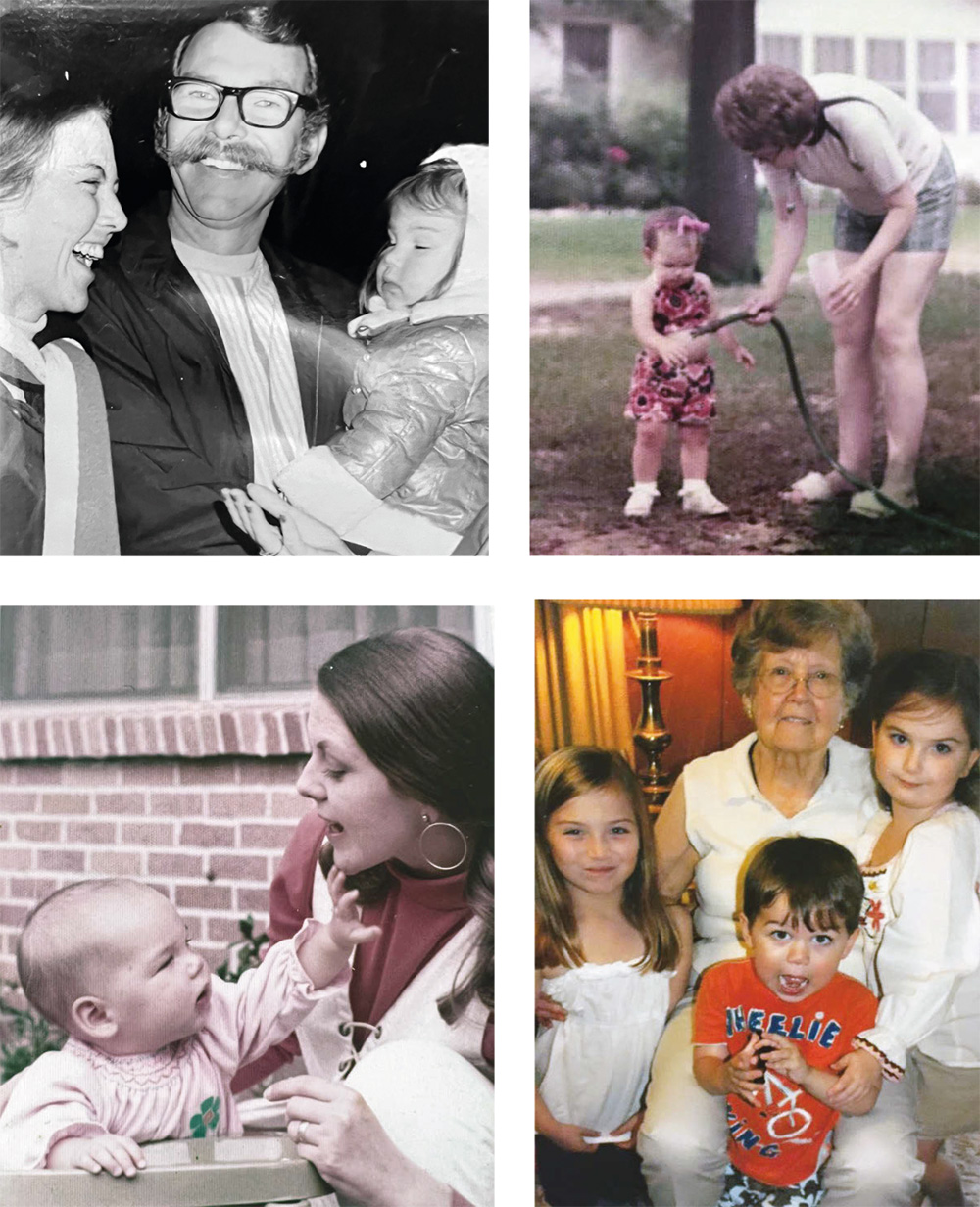

Clockwise from top left: Cathie with her parents, Dorothy and Quincy; Cathie with her grandmother Wilma; Wilma with Cathie’s kids (from left) Madeline, Owen and Julia; Cathie and Dorothy.

Guideposts and fruit flies

At MC, Cathie found a group of Christians who became her people.

“(They) were authentic believers, who lived out their faith, who weren’t about checking the boxes. They had this Bible study that met in the basement of the cafeteria,” where a former penitentiary inmate with a guitar led a Bible study and “talked about real stuff” that Cathie could relate to, she says.

As a freshman, she became a seeker. As a sophomore, she became a little more comfortable in her understanding of God. Then the summer after her sophomore year, she went to Oxford and took a summer class.

“My grandmother sent me with my childhood Bible and a Guideposts (devotional book). And she said, ‘I want you to read this every day while you’re gone.’ And I did it. I like a list, I’m very task-oriented, (and) I would look up the verses in my Bible.”

At the end of the book, “it said if you’ve never prayed the sinner’s prayer, you should pray this prayer. And I can remember being in an apartment at Ole Miss and getting on my knees beside my bed and praying that prayer that was listed,” she says.

“And you could fill out this perforated thing and tear it off (laughs). I remember taking it in there and showing my roommate, and she was a believer. I remember us just sitting there and talking, (and) finally I didn’t feel like I was on the outside.”

Cathie was now a follower of Christ. But she mistakenly believed Christians didn’t need to go to church, and she’d never attended a church that grabbed her. So she just kept going to Bible studies.

Then her fruit flies died.

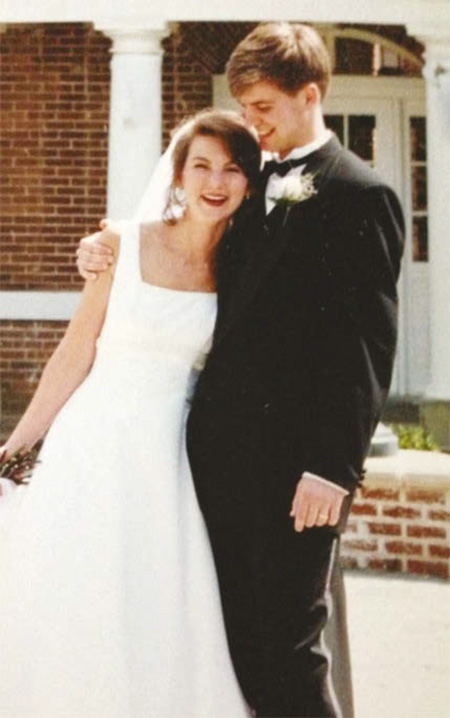

Cathie and Mark were grouped together from day one of med school and were married before their four years were up.

Specifically, her fruit flies for a crossbreeding assignment for a genetics class. “And if they died, you had to start over, and that puts you in the lab in the middle of the night,” she says.

So at 2 a.m. on a Saturday night, technically already Sunday, Cathie and one other female student were working away in the lab. The girl asked if Cathie was going to church in the morning and, when she said no, told her, “I think you’re missing out on a large part of Christianity.”

Because the girl was African American and Cathie had never attended a black church — and because “I was always up for a challenge,” she says — she accepted the girl’s invitation to her place of worship.

Horizon Community Church was located on the I-55 frontage road in Jackson, and it wasn’t for black or white. It was for Cathie.

“I had never seen anything like (it),” Cathie says. “It was folding chairs, it was a contemporary worship service, it was very casual, and it met me right where I was at. And I remember not even being able to sing because I was crying.”

She got involved at Horizon, started going on mission trips, and continued her coursework at MC — which was taking her down a different road than she’d expected.

Cathie (left) and Dr. Shea Moses get creative with hygiene during a 1996 mission trip to Honduras.

‘I just wanted out’

Cathie was enrolled in MC’s pre-med program — but she didn’t know that was supposed to lead to medical school.

“I thought pre-med was like nursing school,” she says. She took a semester of classes, made good grades, and went to her advisor, Dr. Anne Meydrech, to plan her second semester.

“She said, ‘Let me just chart out how your path would look.’ And she starts making this LONG plan, and I’m like, ‘What are you talking about?’”

After recognizing their misunderstanding, Dr. Meydrech said, “You don’t need to sell yourself short.” She urged Cathie to go to med school.

“I wanted out,” Cathie says. “I wanted out of Clinton; I wanted out of my poverty … I just wanted out. If I had not had her as another stabilizing force to say, it’s worth it, (I would not have done med school). She would always prop me up.”

As a senior at MC, Cathie took the MCAT (Medical College Admission Test), made an average score, and got waitlisted. “You had to wait right up until school started (to find out if you got in),” she says.

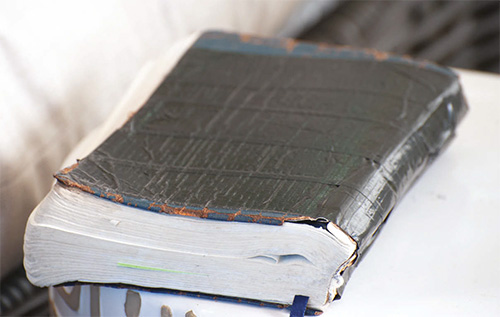

“A lot of what is written in this Bible is from that time period,” she says, gesturing to an old copy of God’s Word covered in duct tape. “I just knew He was going to do it.”

She never got the call.

“I hit a wall,” she says. “I really don’t know how God pulled me through.”

She got a job at Mississippi Baptist Medical Center in Jackson, first as a patient transporter, then as a tech in the echocardiography lab. She saved her money, retook the MCAT — and made the exact same score.

“I went to the (med school) interview and told them I had no plan B,” no wealthy parents or ready-made job at the family business if things didn’t work out, she recalls.

Cathie treating a patient during a mission trip to Cambodia.

This time, she got in. “I was super grateful, super nervous, and elated.”

On her first day of class at The University of Mississippi School of Medicine in Jackson, she was placed in alphabetical order by last name — hers was Prestridge, and she sat two seats down from a guy named Mark Phillippi. Cathie and Mark were also placed in the same work group by last name for things like cadaver dissection.

“I was very distrusting of men” and pushed Mark away at first, she says. “Gradually, we became really good friends. … I think God knew I needed that.

“I learned the difference between confident and cocky from him, because he was very confident, but he wasn’t cocky.”

Mark became her study partner, her lab partner, and in their third year of med school, her fiancé. They wed the following year with only a month left of classes.

“I never would’ve met my husband if I had gotten in (to med school the first time),” she says.

While waiting to find out if she made it into med school, Cathie wrote a lot of notes in this Bible, her favorite, now covered in duct tape.

A pandemic and thorns

After moving to Little Rock for residency (Cathie did pediatrics and Mark did nephrology, aka kidney medicine), then to Birmingham for Mark’s fellowship, the Phillippis returned to the Jackson area in 2004. Cathie worked as a pediatrician at Children’s Medical Group.

Then the COVID pandemic hit.

“My middle child has severe Crohn’s and is on immune suppression,” Cathie says. “My husband was gearing up to be chief of medical at Baptist. … I got nervous for (Julia), having two parents on the front lines.”

So Cathie left her job and stayed home in 2020. She helped her daughter Madeline navigate a weird senior year of high school and helped her sixth-grade son, Owen, with virtual learning. But soon, Warren Herring and Philip Coburn of TrustCare found out Cathie had left Children’s Medical Group and “approached me about a position,” she says.

“I was able to partner with them and create a dream clinic,” TrustCare Kids, which opened in Gluckstadt in January 2021, she says. “They have enabled me to stand on them and create something I never could’ve created on my own. They believed in me and have become dear friends and fierce advocates.”

The clinic is partly primary care, partly urgent care, for children birth through college age. Cathie typically spends a third of her day doing checkups and the rest on acute care for her own patients. “But if there’s a need and I have time, I’ll do urgent care,” she says.

As a pediatrician, Cathie sees plenty of unruly patients, but “a child may act out because of what just happened (at home),” she says. “You see recurring themes. … It’s a lot for a child to hear people constantly at odds.”

Cathie (second from right) serving at Fondren Church.

Cathie also has a heart for children dealing with even deeper traumas all over the world. At Fondren Church, where she is a member, she learned about a ministry called The Hard Places Community, which (among other efforts) serves children at risk for sex trafficking in Cambodia. She’s gone to Cambodia with the organization and treated kids there, in addition to taking other mission trips to places like Honduras, the Dominican Republic and India.

“It grounds me and makes me realize how big the world is,” she says.

It also draws her closer to her Savior, who came to seek, serve and save the lost.

“I want people to know that nothing about Christianity was appealing to me because of a church or a program or someone shaming me,” she says. “When I learned about the humility and the unconditional love of Jesus, that’s what got to me.”

In many ways, it was her struggles that brought her to that understanding of Christ. If she hadn’t been spiritually starving, she might never have reached for the bread of life.

“There are a lot of people who struggle either with childhood trauma, anxiety, depression, self-worth issues, even suicidal thoughts, and there have been times I’ve thought, if I can just get here, it’ll all go away, or if I can just be spiritually mature,” she says.

But in the end, “that thorn in your side is sometimes the thing that draws you closer to God.”

Cathie sees children from birth through college age at TrustCare Kids in Gluckstadt.