By KATIE EUBANKS

Equally yoked

Devon and Jacqueline Loggins fulfill their calling at

Methodist Children’s Homes of Mississippi

Devon and Jacqueline Loggins met in prison — well, sort of.

He likes to joke about it. “It’s the security answer for all my passwords: ‘Where did you meet your spouse?’”

They both were social workers at D. Ray James Prison in Folkston, Georgia.

“Maybe on the second day, I walked past this lady,” Devon says. “I never saw her face, just the back of her. She was standing at a table doing something. And the Holy Spirit in me just went, ‘Wow.’

“When you work in prisons, you can either date your coworkers, and your career will probably go downhill — or you can just marry your coworker. That’s what we did.”

Jacqueline says she and Devon were “equally yoked,” and not just spiritually.

“We speak the same trauma language (because of our work),” she says. “When people get married, they talk about having a lot in common, but (with us it’s) across the board. Our families, our degrees…”

They had another thing in common, too: They weren’t sure they saw themselves staying in prison work.

“(Devon) was the one who initially focused on children (when we thought about changing careers),” Jacqueline says. “We were serving young men coming into prison at 17. It wasn’t 30 (years old) anymore. (We thought) ‘There’s got to be a way we can reach them at an earlier point’ … Even before delinquency.”

Besides wanting to reach young people earlier in their lives, Devon also just wanted to work somewhere else, he says.

“When I first started working in prisons, I was excited. You could tell people what you did, and they’d be super interested in it. And I was making a lot of money. But I was miserable. Now I know it’s because it wasn’t my calling,” he says.

Something that would shake up any kid

Looking at inmates’ records, Devon says, “they all either had childhood trauma or had been in foster care.”

“When people get married, they talk about having a lot in common, but (with us it’s) across the board,” said Jacqueline Loggins, right, of herself and her husband, Devon. The Logginses minister to children at Methodist Children’s Homes —she as a therapist and volunteer, he as CEO.

He and Jacqueline both could relate, in different ways.

Devon is quick to say he was never abused or neglected as a child. “In fact, I was the spoiled baby,” he says. But as a 7-year-old growing up near Kilmichael with nine older siblings, he did go through something that would shake up any kid:

“I found out that my mother and father were really my grandparents, and that those nine older siblings were my aunts and uncles — except one was my mom. I remember moving back to Chicago with (my mom) and butting heads, because I saw her as my sister.”

Jacqueline had four sisters and one brother. For five years, she was in foster care — but only with her brother and one sister. Nobody was willing to take all six siblings together.

“There was always in the back of my mind, ‘Where are they? Are they safe?’” she says.

“I became maternalized, taking care of my younger sister and brother. And trying to be obedient so nothing would happen to split us apart! It changes your whole life.”

She and Devon didn’t know it, but their experiences were preparing them to make an impact on hundreds of children in the future.

‘The kids everybody else says “no” to’

Devon started working at The Methodist Home for Children & Youth in Macon, Georgia, as a therapist, “and the Lord kept promoting me,” he says.

“I fell in love with that organization. I loved helping staff members, team members, figure out how to deal with people in crisis.”

While he was at the Methodist home, Jacqueline worked in the field of domestic violence. When the opportunity came for Devon to move to Methodist Children’s Homes of Mississippi (MCH), Jacqueline supported his desire to be closer to his family in the Magnolia State. That was seven years ago.

Today, they each have found their calling: Devon is CEO of MCH, while Jacqueline teaches social work at Jackson State University and sees clients as a therapist, both privately and through MCH. The Logginses’ house is on site at the agency, on a road that winds through trees dripping with Spanish moss. (The whole campus is 186 acres.)

“His calling is working with the employees (at MCH). Mine is working with children,” she says. “I focus on sexual abuse, child maltreatment, physical abuse, and children in foster care.”

MCH serves more than 150 children per year in three main service areas: group homes on campus (which can serve up to 40 kids total); therapeutic foster care in the community; and a community mental health center.

The agency has also submitted a proposal to the state Department of Mental Health for a permanency assessment center, which would allow kids to stay at MCH for 60 days while getting a comprehensive assessment of their needs — i.e., where they should be placed. This on-campus center would also assess underage survivors of human trafficking.

Jacqueline Loggins, center, with she and Devon’s daughters, Christina (left) and Danielle.

Why is that last part relevant? Well, last year, MCH served six children who were survivors of sex trafficking. Let that sink in.

“About 65 percent of (the children we serve) have significant histories of running away,” Devon says. “Thirty percent have significant histories of substance abuse. Forty percent have significant histories of physical abuse. Eighty percent or more are simply in our care due to neglect, which is failure (of the parents) to provide for basic needs — food, shelter, medical, dental.”

And, “one hundred percent (of the kids we serve) have a mental health diagnosis. And that’s what makes (our foster care) therapeutic,” Devon says. “I would advocate that all kids in foster care receive therapeutic treatment.”

The average age for a kid entering MCH programs is 15 years old. The average number of prior placements in foster homes, group homes or the like? Also 15. So a 15-year-old child could enter MCH with 15 previous “homes” under their belt.

“We take the kids everybody else says ‘no’ to,” Jacqueline says.

Devon confirms: “That’s our reputation. Sometimes that hurts us. Our data sometimes is not the best. (But) if we don’t (take those kids), from our experience in the criminal justice system, they will be the kids kicking in your front door or robbing you or hurting you,” he says.

“We don’t believe in changing kids. We believe in that old adage of planting seeds. And the Lord waters the seeds. Many times we don’t see it. The average stay (at MCH) is six to nine months.”

“But to reach that one (child) makes you feel good,” Jacqueline says.

Devon Loggins, left, with Christopher, a Methodist Children’s Homes alumnus who joined the U.S. Army

and “adopted” Devon and Jacqueline.

A prime example: A young man named Chris who grew up in an MCH group home and, at 18, joined the military. He’s now two years into his service and stationed at Fort Hood, Texas.

“He got his driver’s license after joining the military, he bought a car, and he just drove here from Fort Hood the other day and is staying with us while he’s on leave,” Devon says.

“I’m proud to say he adopted us,” Jacqueline says. “He calls me Mom. He woke me up this morning and said, ‘I’m hungry, Mom.’”

“That’s when (what we do) counts, is when they leave the system and enter the real world,” Devon says. “We think we know everything at that age, and we don’t.”

A lot of MCH kids have “adopted” the Logginses. So many, in fact, that keeping up with all of them is tough, Jacqueline says.

“You know how they change phones all the time,” Devon adds. “But you’re embarrassed to say, ‘Who is this?’ (when they call).”

Devon and Jacqueline also have three grown children of their own: Christina, an attorney; Danielle, a restaurant manager; and Jordan, an officer with the Jackson Police Department.

‘How do you want to be remembered?’

Devon quotes psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner: “Every child needs at least one adult that is irrationally crazy about him or her.”

Only one Person is irrationally crazy about every child.

“We know the love of Jesus Christ is unconditional,” Devon says. “And research shows there’s so many things you can try to do to heal from childhood trauma. But the only thing that will help is a healthy relationship. And that relationship starts with a relationship with the Lord.”

Devon recites another quote, this one the MCH mission statement: “Through Jesus Christ, Methodist Children’s Homes brings hope and healing to hurting children in Mississippi.”

Devon and Jacqueline Loggins, back, with their godchildren Aiden, left, and Aubrey.

On our own, we can’t do anything. But those first three words, ‘Through Jesus Christ … ‘

MCH shows the love of Christ not only via social services, but personal touches as well. Most kids keep their bags packed long after they arrive — they’re used to being shuffled around — but Jacqueline and another volunteer will decorate and paint bedrooms in advance to make them feel like home.

“It isn’t sterile,” Jacqueline says. “If it’s a girl’s room, we make sure there’s lots of fluffy stuff and pinks. Lewis Furniture in Clinton has donated so much.”

(“They know us because my wife also likes to shop there,” Devon deadpans as Jacqueline smiles with glee.)

Devon says the Jackson community has helped make MCH a productive and powerful experience for the kids. Volunteers come in and lead weekly Bible studies. Bank representatives teach financial literacy. Therapists, including Jacqueline, provide counseling for the children at no cost.

Eventually, children leave the MCH group homes or age out of MCH’s therapeutic foster care. The question is, what will they take with them from their experience? What will they say as adults when they look back?

Devon hopes they remember MCH as a place where they experienced the love of God. He takes each and every MCH alumnus who’s “adopted” him to heart. Knowing that kids are watching him makes him want to be a better person, he says.

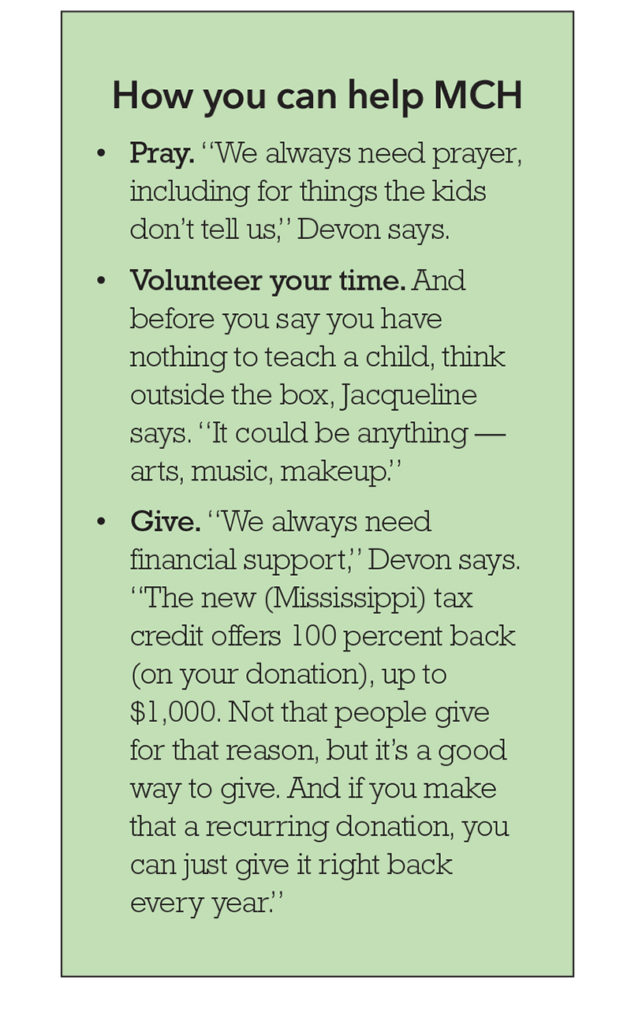

“My old CEO said to me, and this has always stuck with me: ‘Devon, how do you want to be remembered?’”