MISSION MISSISSIPPI

Reconciliation reaches far beyond metro Jackson

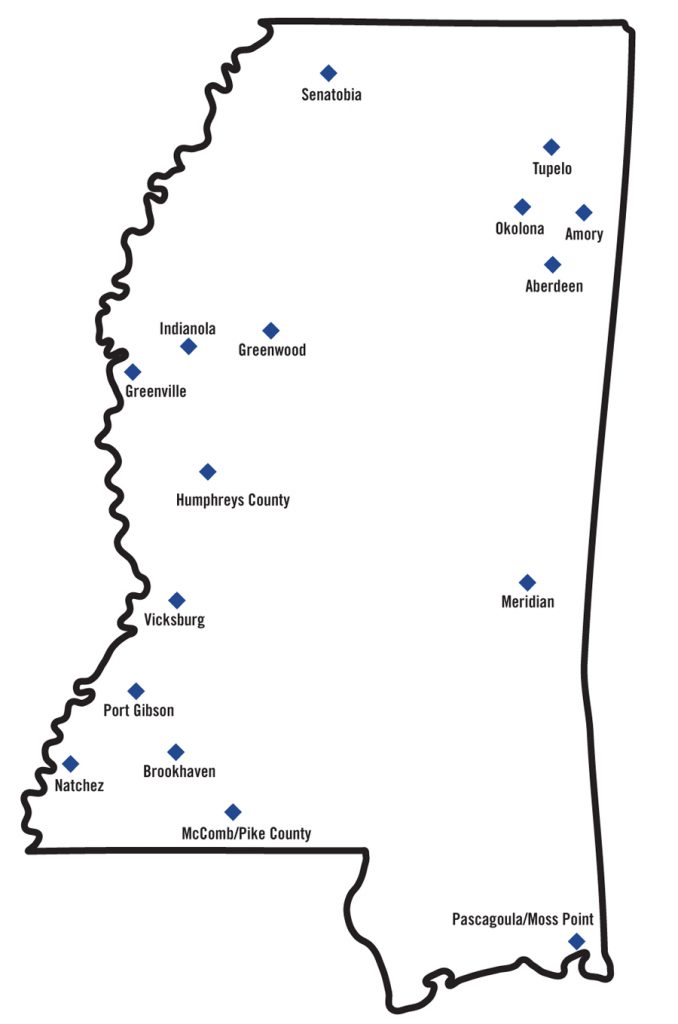

Mission Mississippi has chapters all over the state, each of them with stories of people coming together across racial and denominational lines for the glory of God.

There are active chapters in Aberdeen, Amory, Brookhaven, Greenville, Greenwood, Humphreys County, Indianola, McComb/Pike County, Meridian, Natchez, Okolona, Pascagoula/Moss Point, Port Gibson, Tupelo and Vicksburg – with a new chapter recently launched in Senatobia.

However, the organization works in all 82 counties.

The chapter in McComb, once a hotbed of racist activity, has been persevering for nearly two decades.

To tell all the stories of Mission Mississippi would take a book – one that Executive Director Neddie Winters hopes to get published in the next few years. But for now, here are a couple of “Mission Mississippi moments,” as Neddie calls them – stories of reconciliation and surprises – from the Pine Belt and the Delta.

REBUILDING IN MERIDIAN

Stacey Miller, Wade Phillips and Beth Sharp make up the leadership team of Mission Mississippi’s newly relaunched Meridian chapter.

Stacey Miller grew up knowing what her father stood for.

“He didn’t let race stop him from helping someone in need,” she said of her dad, the Rev. Charlie Miller.

Stacey’s parents attended an African-American Christian college in Texas during the civil rights movement and toured with a gospel singing group based at the college. Her father later became a pastor, and the family moved to Mississippi in the mid-’70s.

On more than one occasion, white women approached Charlie for help – something a black man had reason to fear. But he came through.

“My mother tells me they had just moved to Mississippi (and) this white lady came to the door. Her boyfriend had put her out of the car, and she needed a ride home.”

Stacey’s mother, Jinnell, hesitated, but she and Charlie ultimately decided to drive the woman home together.

Another time, “this white young lady … in California got my dad’s phone number … and said something was going on with her boyfriend and she needed some help. She was stranded. And so my dad used the Church of God yearbook and found some white pastors out in California and … hooked them up with this white lady.

“That’s what I mean (when I talk about) my father’s legacy.”

In 2003, Charlie Miller died in the workplace shooting at the Lockheed Martin assembly plant in Meridian. News reports from the time quote Lockheed Martin employees describing the white shooter as a racist who had threatened to kill African-Americans before. He began the killing spree after walking out of a diversity training session. Five of the shooter’s six victims were black, though most of the injured were white. He also killed himself.

After losing Charlie to hatred and violence, Stacey said, her mother refused to give in to animosity.

“I give my mother credit. She was also a minister. It could easily have been another Ferguson. (But) when the media asked her who she was mad at, she said she was mad at sin,” Stacey said.

The Millers started holding racial reconciliation activities each year in Meridian in Charlie’s honor.

Then five years ago, Stacey was being interviewed by a TV journalist, Wade Phillips.

“He was interviewing me, but –“

She could tell Wade was interested in racial reconciliation on a personal level – especially when she saw him reporting on the 20th anniversary of Mission Mississippi from Jackson.

Wade grew up in the Scott County community of Sebastopol, Mississippi in the ‘80s.

“(The civil rights movement) wasn’t that long before I was born,” he said. “(There was) a lot of resentment from white folks about what had happened. (Racism) was just the air that I breathed in small-town Mississippi at the time.”

But Wade read his Bible. And he played high-school football.

“(There was) a group of black guys on the team, we were close friends, and the more I was around them, the more I realized these guys aren’t different than me. … My coach was a black guy – I think that helped. I’ve had authority figures in my life who were black, and that’s helped. My boss at the TV station for almost the whole time I was there was a black guy.”

As Wade grew in his faith, took seminary classes and raised a family, he continued to grow in his belief that one couldn’t “read the Bible honestly” and think racism was okay.

When he interviewed Stacey for the news, she and Neddie were wanting to relaunch the Meridian chapter of Mission Mississippi.

Fast forward to today: Wade, Stacey and others have successfully relaunched the Meridian chapter and have held five prayer breakfasts so far this year, with one more planned.

Wade, who left his broadcast career and is now assistant pastor at Northcrest Baptist Church in Meridian, said Mission Mississippi has fostered some surprising interracial relationships there – including among the chapter leaders.

Stacey agreed.

“In June we got into a good discussion while we were planning the July (prayer breakfast). … That would not have happened or could not have happened if we hadn’t been together first to build a relationship,” she said.

“‘Why is there a Black Lives Matter movement?’ That’s a question that came up. ‘What’s the difference between the term “black” and “African-American”’?

“We have a core (leadership team) now where we feel we can have those conversations. (But) if you get (to the discussion) before the relationship, somebody’s going to leave.”

DOLPHUS WEARY GOES TO MARKS

This year, Dolphus Weary – previous executive director of Mission Mississippi and a longtime Rotarian – “put out feelers” to different Rotary clubs throughout the state to see if he could come speak.

The club in Marks, located near Clarksdale in the Delta, said they were all booked up.

Dolphus called an acquaintance who had connections in Marks, and that person put in a good word for him. A spot opened up on the club’s calendar – but Dolphus was a little nervous.

“I knew they had no black members,” he said. “I was a little concerned about that.”

His anxiety didn’t exactly abate when he and his wife, Rosie, started the drive to the meeting place: Wilson Lake Country Club, located outside of town “down a long, mile and a half to two-mile road going into the woods.”

Keep in mind, this is a man who had literally written a book about Mississippi titled “I Ain’t Going Back!” He came back, like folks of all races tend to do, but he knew what communities like this were known for at certain periods of time.

“Lord, why are we going up in here?” he thought.

Dolphus and Rosie arrived at the venue. He spoke. And the Rotary club loved it.

“It was one of the best times of my sharing and the interaction with the questions (afterward). I couldn’t leave without them saying, ‘We want you to come back. We want you to come back,’” he said.

“That just goes to show, we can’t make snap judgments. I found some warm, wonderful people there and my mind was turned around.”

HOW TO GET INVOLVED

From statewide events to round-table discussions and days of dialogue, there are plenty of opportunities for people to participate in Mission Mississippi.

MissionMississippi.org lists the local chapter locations and meeting times. Most chapters meet regularly for a prayer breakfast or lunch, and the frequency varies by the group, Neddie said.

If you’re interested in starting a new local chapter or can’t find the information you’re looking for online, call Mission Mississippi at 601-353-6477.