By Marilyn Tinnin

Flonzie Brown Wright

Pioneer, Visionary, and Steel Magnolia

Flonzie Brown Goodloe Wright is a beautiful lady who looks much younger than her 75 years. Like most Southern women, she loves to tell you about her children, her upbringing, and her family tree. She is gracious, kind, and energetic. She entered the working world during a time there were few professions outside of school teaching where African-American women assumed leadership roles.

You could say Mrs. Wright is one person who has the leadership gene inscribed in her DNA in all caps. When she won a race for Election Commissioner in Madison County in 1968, she was the first black woman elected to office in Mississippi since Reconstruction. She rose to prominence as a leader in the Civil Rights struggle of the 1960s and 1970s, and to this day, has a very active career writing and speaking on the subject literally around the world. Flonzie insists, “I didn’t choose the movement. The movement chose me.”

You could say Mrs. Wright is one person who has the leadership gene inscribed in her DNA in all caps. When she won a race for Election Commissioner in Madison County in 1968, she was the first black woman elected to office in Mississippi since Reconstruction. She rose to prominence as a leader in the Civil Rights struggle of the 1960s and 1970s, and to this day, has a very active career writing and speaking on the subject literally around the world. Flonzie insists, “I didn’t choose the movement. The movement chose me.”

From her childhood, Flonzie had been surrounded by nurturing parents, a strong faith community, and mentors who instilled within her, what she calls, “fireside family values.” At the Old True Light Missionary Baptist Church in the Farmhaven Community of Madison County, she heard Bible stories that inspired her, and she sang the hymns like “Standing on the Promises” that filled her with the assurance of God’s faithfulness and love for her. It was not a stretch for her to understand a loving heavenly Father because her own father was very present and very involved in her life and in the lives of her two younger brothers.

Although racism and injustice and the unresolved decades-old issues were brewing all around her in her early years, Flonzie’s parents shielded their children from it. Hate or victimhood was never implied or verbalized. “They taught us values. They taught us love of family, and they taught us how to make a way out of no way.” She learned a tireless work ethic, and she adds that she had no idea her family was poor until she was much older.

Although racism and injustice and the unresolved decades-old issues were brewing all around her in her early years, Flonzie’s parents shielded their children from it. Hate or victimhood was never implied or verbalized. “They taught us values. They taught us love of family, and they taught us how to make a way out of no way.” She learned a tireless work ethic, and she adds that she had no idea her family was poor until she was much older.

She speaks with great respect and affection of her parents. “They taught us how to believe in ourselves and that we didn’t have to be looked down on and neither did we look down on anyone else, and that anything anyone else could do, we could, too. They were so dedicated to seeing that their children had a better opportunity than they had had.”

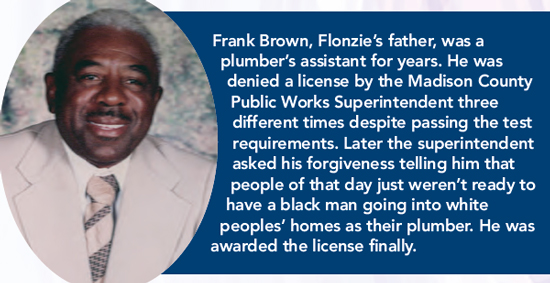

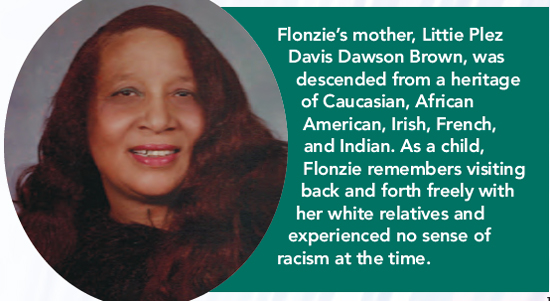

Litty Brown, Flonzie’s mother, was a talented seamstress. She prioritized family and chose to be a stay-at-home mom, but her sewing did provide a modest second income. Flonzie’s father, Frank, was a plumber’s assistant who made $18 a week. Somehow, he and Litty made it work. Although things were always tight, the Brown children attended Holy Child Jesus School in Canton where they received an excellent education from the Franciscan sisters in their elementary years.

Litty Brown, Flonzie’s mother, was a talented seamstress. She prioritized family and chose to be a stay-at-home mom, but her sewing did provide a modest second income. Flonzie’s father, Frank, was a plumber’s assistant who made $18 a week. Somehow, he and Litty made it work. Although things were always tight, the Brown children attended Holy Child Jesus School in Canton where they received an excellent education from the Franciscan sisters in their elementary years.

Flonzie married her high school sweetheart in 1958. They moved to California where they started their family, but the marriage dissolved just a few years later. Flonzie returned to Canton, to her parents’ home knowing that she would have to find a way to support herself and her three children.

The state she came home to did not seem like the state she had left years earlier. Medgar Evers had recently been murdered, and that story filled the front pages of every newspaper in the country. Busloads of college students from the Northeast were descending on Mississippi in an effort to help black residents register to vote. “Jim Crow” was alive and well, and despite the edicts handed down from Washington, D.C. regarding voting rights, there was resistance and a multitude of ways city governments managed to preserve the status quo. All eyes were on Mississippi where racial unrest was in full swing.

You could call this Flonzie Brown Goodloe Wright’s defining moment.

Joining the Movement

This was 1962, a period before women entered the workforce in mass and competed with men at every level in the marketplace.

Finding employment as a black woman was an unusually difficult feat at that time, but Flonzie had been reared to be independent. She was determined to provide for her children. In the beginning, she worked here and there piecing things together as best she could.

But in her heart and in her inmost soul, she knew that the God to whom she had been introduced even as a little girl was as powerful as ever and that the “fireside values” she had learned in her home were still true. It was that faith that kept her going in the middle of a great deal of uncertainty about her future and the future of her children. She will be the first to tell you that it was God who got her through those first two years back in Mississippi when the political landscape was shaky and she was a single mother of three trying to come to grips with life and purpose.

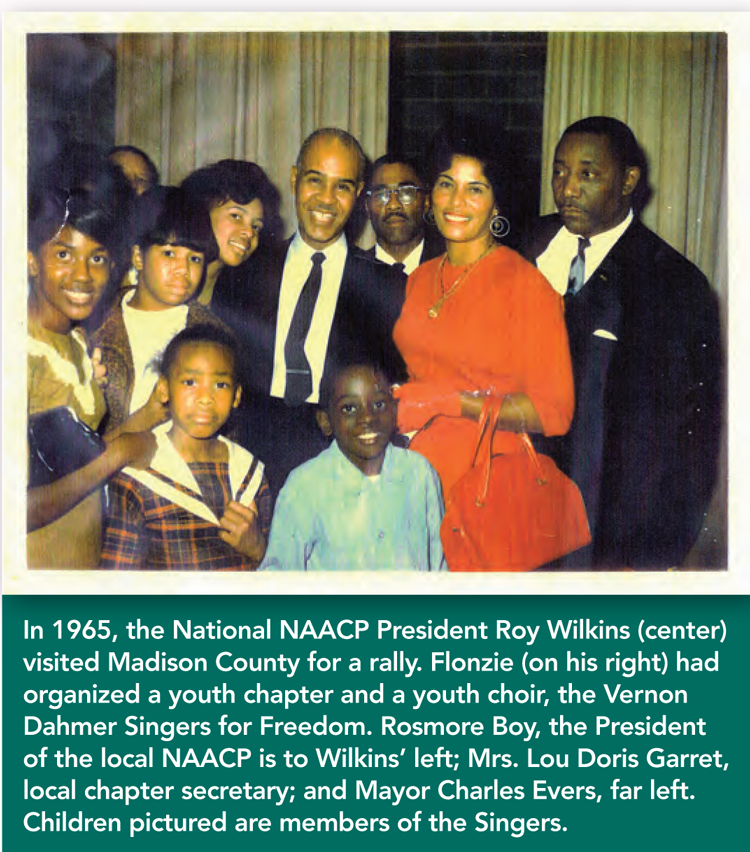

When the NAACP office opened in Canton, she accepted a job there for $25 a week. Although her title was “Director,” she was a one-woman show who handled the books, trained the volunteers, recruited members, and promoted voter registration. None of that was easy. The business of passing the special test devised as a way to keep blacks off the voter rolls made her job much more difficult. It was an ugly struggle.

When the NAACP office opened in Canton, she accepted a job there for $25 a week. Although her title was “Director,” she was a one-woman show who handled the books, trained the volunteers, recruited members, and promoted voter registration. None of that was easy. The business of passing the special test devised as a way to keep blacks off the voter rolls made her job much more difficult. It was an ugly struggle.

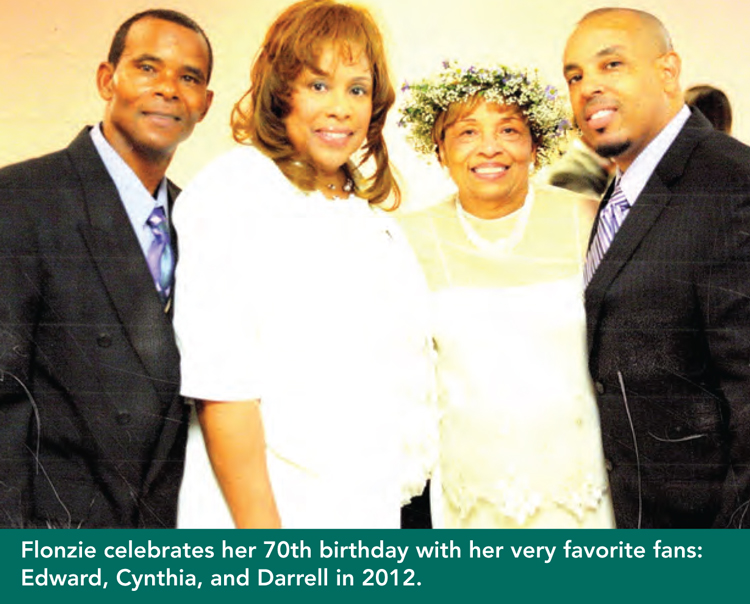

Personally, however, she had learned well from her parents how to stretch a nickel and it was during this time she perfected the art! She sent her offspring, Cynthia, Edward and Lloyd Darrell to Holy Child Jesus School, the same private Catholic School where her parents had sent her years before. No matter what else was reeling around her, she managed to be a very intentional mother.

As time went by and the Civil Rights struggle continued to dominate the headlines, Flonzie’s job at the NAACP morphed into a calling, or as she says in her book “an assignment.” She distinguishes between a job and an assignment this way—“The first is 24/7, and the other is a lifetime!”

She had a big-picture vision of why racial equality mattered. She also had a gift for putting words to her thoughts—she could definitely articulate better than most—and so, she was frequently called on to go beyond her administrative duties. She was speaking, training, studying the law, and just helping out a cause she completely believed was right. She barely realized that her “assistance” was quickly becoming a part of “leadership of the movement.”

She wasn’t looking to make headlines and she was slightly surprised when she did. After all, she was giving her task 100% effort just as Frank and Litty Brown had taught her to do.

Walk Without Fear

In 1966, James Meredith’s historic “Walk Without Fear” was interrupted outside of Hernando by the sinister motives of a white supremacist that shot Meredith three times in the leg. When the news reached other leaders of the movement, several national leaders, including Dr. King, decided to start where Meredith was stopped and continue the walk all the way to Jackson, Meredith’s intended destination.

Of course, the news inspired other supporters to join the march, and as the group progressed South, Dr. King made a call to Flonzie at the NAACP office in Canton requesting her assistance. He wanted her to find overnight housing for 3,000 people, and, oh, by the way, they not only needed a place to sleep but a meal as well. She confidently assured Dr. King that that would be no problem. However, she admits to a severe attack of “knocking knees” as soon as she hung up the phone. How in the world?

She enlisted the help of almost everyone she knew, who in turn put out the word to their friends and local church congregations. “Cook a pot of stew; cook a pot of greens; cook a skillet of cornbread”—everybody did what they could. Holy Child Jesus School opened their gymnasium, and somehow Canton’s black community had a plan to accommodate the multitude. And it came together almost like the loaves and the fishes.

Flonzie introduced Dr. King to the standing room only mob that gathered on the steps of the Madison County Courthouse. She recalls that he spoke softly and simply. His message of non-violence was moving and inspiring. It appeared that all was going to be peaceful—at least it was in that initial moment.

Sadly, despite King’s emphasis on non-violence, conflict erupted later that evening between the crowd and the state troopers who had been assigned to keep order. In Flonzie’s book, Looking Back to Move Ahead, she gives full detail of “mass confusion” amid tear gas and the crush of the crowd. It was frightening, to say the least, but it did not deter her commitment to the cause.

Sadly, despite King’s emphasis on non-violence, conflict erupted later that evening between the crowd and the state troopers who had been assigned to keep order. In Flonzie’s book, Looking Back to Move Ahead, she gives full detail of “mass confusion” amid tear gas and the crush of the crowd. It was frightening, to say the least, but it did not deter her commitment to the cause.

It was an unfortunate event and one that should not have happened. Order returned, however. Dr. King rallied the marchers, and the next day the march proceeded toward its destination peacefully.

Further Involvement in the Civil Rights Movement

Beginning in the Eisenhower years, Congress had passed numerous bills making discrimination based on race illegal. Whether it pertained to employment, educational institutions, or other public places, there was to be no qualifier based on skin color. And yet, there was still a great deal of resistance. Creative ways around the law continued in many places, and especially in the South.

When Flonzie accepted her first job at the NAACP office in Canton, her parents were very concerned for her safety. Though less worried than they were, she was aware that she was in a place of potential danger. She felt very “called,” but at the same time, she felt quite responsible as a mother to be sure she was there for her three children.

She describes a conversation between herself and that voice in her heart when she argued with God. She reminded Him (as if He had forgotten) that she had three children and did not need to be in harm’s way. That still small voice said, “I know all that. I am with you. Although you will never be rich, you will always have what you need, and I am with you. You’ve got to go.”

She describes a conversation between herself and that voice in her heart when she argued with God. She reminded Him (as if He had forgotten) that she had three children and did not need to be in harm’s way. That still small voice said, “I know all that. I am with you. Although you will never be rich, you will always have what you need, and I am with you. You’ve got to go.”

Once Mrs. Wright caught the passion for making a difference, she was tireless in her pursuit. Others recognized her gifts and called on her to go here, go there, and organize this program and that program. She quickly became an expert on the issues and the law. She had been taught by her parents not to do things halfway. If she committed to something, she was all in, and she was more than all in on opening doors of opportunity to those she felt had had them locked and barred for too long.

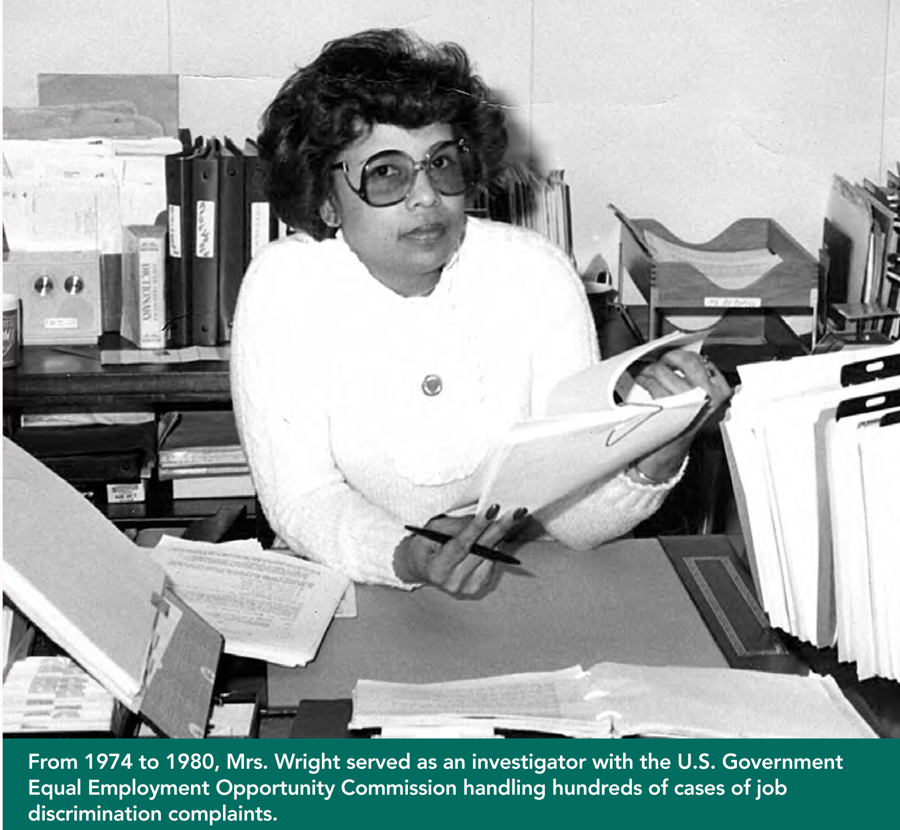

In her very long tenure of devotion to the cause of Civil Rights, she worked in just about every area. She worked with adult education helping at least 12,000 students receive their GED and many of those went on to higher education. She was in the Head Start initiative from its preparation; she both wrote programs and helped train people for jobs in numerous vocations. She worked for years at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission handling investigations of job discrimination. She had to study the laws in order to know what was lawful and what was not. She also had to employ extraordinary communication skills as well as extraordinary people skills.

At this point, she could probably run most any corporation. She has truly earned her stripes on every level. She is well deserving of her prominent place in both the Smith Robertson Museum and the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum.

Connecting the Dots

In the present moment, newspapers, cable news, and the Internet are a conglomeration of accusations, anger, and vitriol. Flonzie Brown Goodloe Wright displays none of that. She has seen it all; she saw the beatings, the animus, the injustices, and she is not bitter.

And why is that?

She admits that when she began to write her book, she had thought it would be so easy. After all, she had lived history and she had so many true stories to tell. Surprisingly, it was not easy at all. As she began to write, she discovered that she had a lot of anger, and it got in the way of her storytelling. Maybe all that anger was suppressed at the time because she felt so called, and she just kept going to the next thing she needed to do. But now she could feel it. She had to put the whole project on hold twice while she dealt with painful memories that needed to be healed.

Looking back that was probably healthy because she dealt with every single thing. Her faith and her relationship with the Lord were actually deeper than any animosity she still harbored over the injustices of the 1960s. That was a reason in itself for writing her book.

Looking back that was probably healthy because she dealt with every single thing. Her faith and her relationship with the Lord were actually deeper than any animosity she still harbored over the injustices of the 1960s. That was a reason in itself for writing her book.

Writing was also a cathartic experience. It was cleansing. It was healing. Her book is well titled, Looking Back to Move Ahead. I suggest you buy it and read it before you visit the Civil Rights Museum.

The Role of Christian Faith

Flonzie Brown Wright has two favorite Biblical passages. The first is Psalm 23. Like many of us, she learned it as a child. She cherishes the thought of “MY” shepherd, the concept of “green pastures,” and she can testify to the fact the Lord does continually restore her soul.

She has walked through more than a little adversity in her life, and each time God’s faithfulness has helped her pick up the pieces and keep going. Losing her oldest son to a heart attack in 2014 was one of the hardest things she has ever had to confront, but even there she has a reason to give thanks and to see the Lord’s presence as her Shepherd and soul-restorer.

Edward, her middle child, was a truck driver and a happily married man of 54. He lived in Louisiana but frequently made runs to Jackson. He called his mother one evening and said he had a delivery to make in Jackson early the next day and asked if his “favorite mother” might have breakfast with him. Of course she would, and she cherished the time they had together. This particular time seemed more special than most.

Edward, her middle child, was a truck driver and a happily married man of 54. He lived in Louisiana but frequently made runs to Jackson. He called his mother one evening and said he had a delivery to make in Jackson early the next day and asked if his “favorite mother” might have breakfast with him. Of course she would, and she cherished the time they had together. This particular time seemed more special than most.

He shared how happy he was at that moment in his marriage and in his career, and he expressed such appreciation and love for the mom who had given so much to him—deep roots, lasting values, and more. Fifteen hours later she received the call that he was gone.

Her other favorite bible passage she quotes word for word as well. Luke 22:31 says, “Simon, Simon, behold, Satan demanded to have you, that he might sift you like wheat, but I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail. And when you have turned back, strengthen your brothers.”

She says, “To me, that’s saying that in this thing called life, you are going to run into all kinds of situations and obstacles where you are going to have to step out and help other people. To me, that’s a call to action. So, even though we are confronted by demonic obstacles, we have to know that Jesus is praying for us.”

Remembering that makes all the difference.

The Bucket List

Flonzie is in no way “retired,” despite her age or the status on her Social Security profile.

“The phone just rings. People ask me to come, and when they ask me my fees, I ask them where their money is coming from. If they tell me they are just getting started and don’t have much money, I say, ‘I won’t charge you anything. If the money is coming from an institution, I just ask for travel expenses and a table where I can sell my book.”

“The phone just rings. People ask me to come, and when they ask me my fees, I ask them where their money is coming from. If they tell me they are just getting started and don’t have much money, I say, ‘I won’t charge you anything. If the money is coming from an institution, I just ask for travel expenses and a table where I can sell my book.”

In the back of her mind, she remembers that conversation with God when He told her, “Although you will never be rich, you will always have what you need.” She has lived long enough to have experienced his faithfulness to that promise.

She does think a lot about the future of her state and its young people. She definitely has a bucket list of wants and a good bit of what she calls “fireside values” that she highly recommends as an antidote to much of what ails our culture today.

“I want better education for our children. I want a broader range of education – I want our students to walk out of those schools with a degree in one hand and a real good history background in the other hand. How can we merge those together? I want old-fashioned values in the home. In our home, we did not eat supper until Daddy came home and we could all eat together. We had chores. We had to learn Bible verses. We got our homework done and our clothes laid out for the next day. That’s how we did it then and it worked. I just want the young generation back in the home, off the streets, and I want the fathers raising their own sons, taking them to the park, throwing the ball with them, teaching them how to be a man, a good husband, and a good father.”

She ends her book with a chapter of healing the land. She speaks of hope and eternal values and the commitment of Believers to each other. That is not a black or white thing—it’s a we-us-together thing. And it can be our collective future.

“If my people who are called by my name will humble themselves and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways; then will I hear from heaven, and will forgive their sins, and I will heal their land.” 2 Chronicles 7:14.